The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (Movie) 1978

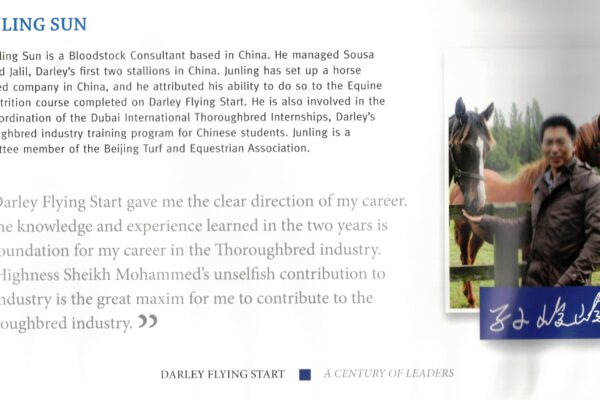

Featured Image: Tommy Lewis in the title role of the movie as Jimmie Blacksmith

‘The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith’ was partly filmed at Arthur and Kathleen Pring’s property ‘The Hawthornes’ at Kars Springs to the west of Scone. This is the same area frequented by teacher and later international author Havelock Ellis almost 100 years before. Ellis wrote with sympathetic eloquence about the country. It had probably changed but little in the intervening century? Fred Schepisi and his ‘location spotter’ team selected the mountainous terrain devoid of modern characteristics such as power ‘poles and wires’. The site needed to be isolated. Other sets were a bark hut at John Archibald’s neighbouring property ‘Dunwell’. A Bush Fire Water Truck was co-opted to provide rain on demand. Further shooting took place at Rouchel where Anne McMullin recalls the old slab cottage at ‘Bingeberry’ (1864) used as a prop.

The director of the movie was Fred Schepisi now an Oscar Winning Hollywood celebrity. The cast included such well known stars as Ray Barrett, Jack Thompson, Angela Punch and Ruth Cracknell. Tommy Lewis played the part of Jimmie Blacksmith. Local SCADS players co-opted for the scene at the ‘Hawthornes’ homestead were Fred Winter, Ruth Logan and Tom MacMurray. Three month old baby Blake Flaherty (daughter of Ros) was selected by Rhonda Schepisi to play the child born to the character Gilda Marshall who was portrayed by Angela Punch.

Nancy Gray wrote in the Scone and Upper Hunter Historical Society’s Newsletter of September 1977:

“Historically the Sparkes Creek Valley is excellent, as Jimmie and Joe Governor, whose lives give Keneally the basis theme of ‘The Chant’, were familiar with the Liverpool Range that towers above the Creek, and walked its ridges and gullies with assurance.”

Review of Movie by Roger Ebert, February 10, 1981

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-chant-of-jimmie-blacksmith-1981

One of the wonders that a good movie can sometimes achieve is to take us entirely outside the framework of the society to which it will eventually be shown. Fred Schepisi’s “The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith,” an Australian film about a half-aborigine who goes on a savage murder spree against whites, is a movie like that. Its story is told entirely in the moral terms of the raw Australian outback of about 1900, and the racial attitudes in the movie are firmly drawn from that period.

That’s one of the things that makes the movie fascinating. Too many movies about race are established in the past but contain the attitudes of the present — so that, for example, Muhammad Ali as a slave in “Freedom Road” need say nothing that Muhammad Ali as a TV star in 1979 did not feel like saying. And so we get contemporary pieties about the past, and they do great damage because they hide the past itself from us.

“The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith” re-creates its other time so well that we come out of the theater in substantial identification with its hero. We do not condone him, but we understand him. Jimmie Blacksmith in this movie kills a large number of innocent white people, including women and children. But he does not do so for reasons of the radical politics of hate. He does so, basically, because racism has driven him mad without even giving him the vocabulary he needs to be able to say that it is racism.

Jimmie is a half-breed, born of an Aborigine mother and a white father who took his sexual convenience in the nearby Aborigine settlement. Jimmie is raised by a white missionary couple, who advise him to marry a white girl from a nearby farm “because then your children will be only a quarter black, and your grandchildren hardly black at all.”

This advice — that Jimmie’s salvation lies in the dissemination of his genes until they lose all power in the white genetic pool — is, when you get right down to it, as genocidal as what Jimmie eventually does. It would just take longer and not involve murder.

Jimmie, meanwhile, works hard and is a good laborer, but is smarter than his white bosses (one illiterate farmer will not write a recommendation for him because he does not want to admit he cannot write). As an assistant to a white policeman, Jimmie witnesses the killing of blacks by whites. In his own life, he is closer witness to the destruction of his hopes and dreams by a society that not only does not care about him, but is so myopic as to not even quite know he is even there.

The final blow comes after Jimmie’s white wife has their baby, and it is all white — obviously not Jimmie’s. Then he goes on his mad killing spree, which is, I understand, based on a historical event. “The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith” has finally arrived at Facets Multimedia, two years after creating a sensation at Cannes (where it was the first Australian film accepted as an official entry). It is, among its other accomplishments, powerfully photographed and well-acted.

But more than anything else, it is valuable because it deals with its materials in the terms of the period in which it is set. I found no message in the movie, and no contemporary political attitude reflected in the events of the past. What I found instead was much more rare, a film concerned with showing us how people felt, acted and lived 80 years ago. To know where we are, we must begin by knowing where we came from.