About The Wonnarua

Featured Image: Aboriginal Tribes in the Hunter Valley

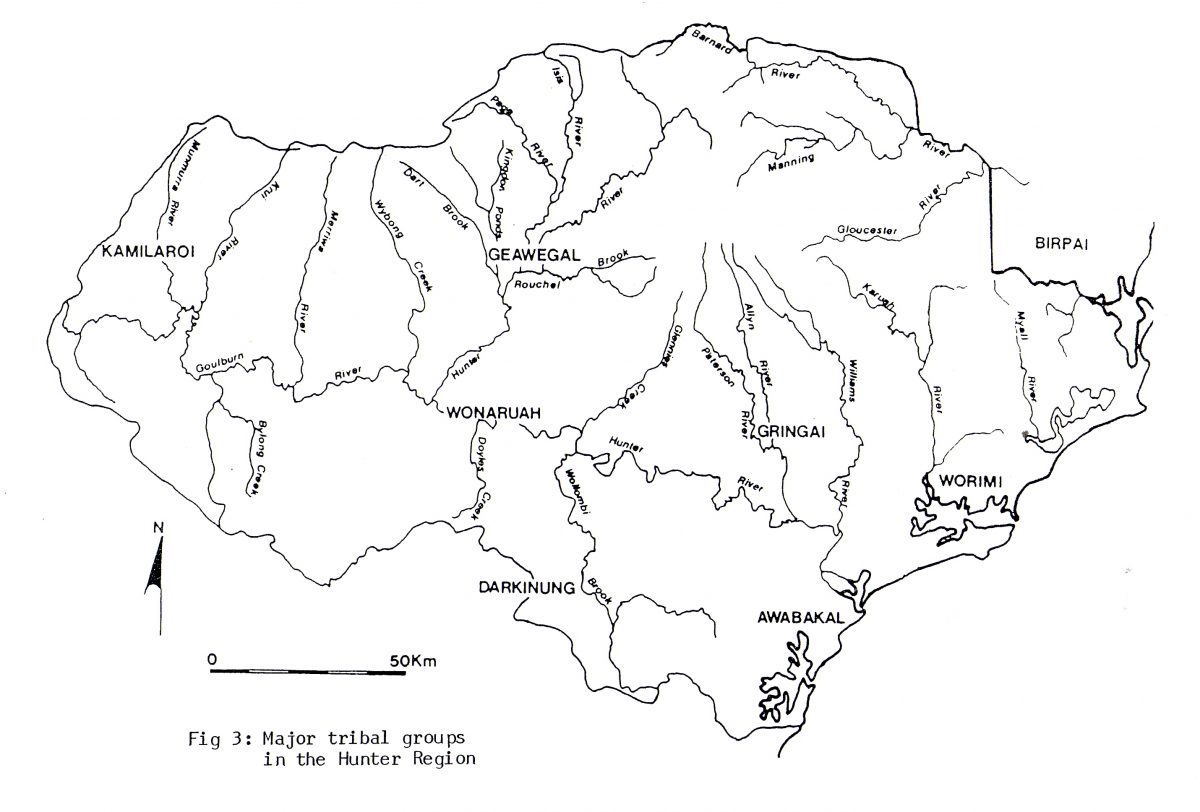

We acknowledge the Wannarua people as the traditional owners of the land in the Upper Hunter. The Wonnarua people are united by a common language, strong ties of kinship and have survived as skilled hunter–fisher–gatherers in family groups or clans scattered along the inland area of the Upper Hunter Valley. Their traditional territory spreads from the Upper Hunter River near Maitland west to the Great Dividing Range towards Wollombi. The local Dartbrook-based tribe was the ‘Tullong’ with the ‘Murrawin’ on Pages Creek.

Meaning people of the hills and plains the Wonnarua were bounded to the south by the Darkinjung, to the north–west by the Nganyaywana, to the north–east by the Awabakal, and to the south–east by the Worimi peoples. The Wonnarua also had trade and ceremonial links with the Kamilaroi people. Their creation spirit is Baiami, also known as Koin, is the creator of all things and the Keeper of the Valley.

The Valley was always there. It was there in the Dreaming, though mountains, trees, animals and people were not yet formed. The river as know it today was yet to be born. Everything was sleeping. For some unknown reason there was movement. This movement stirred from invisible forces. It was not physical. Sky spirits were opening their eyes, eyes that had been sleeping in chasms of eternity. Some spirits recognised their belonging, others did not. Some fought, some slept on and others held council to consider, bargain, compromise and ultimately to create.

Only after much time would the finished product be ready. The spirits interacted, shaping what was nothing, into something. They gave life to the whole valley. Nebulous forms began to take shape. Some forms flew, others crawled, hopped and walked, while gigantic forms were satisfied to stay in one place. Everything was ready. But something was missing from the valley floor, something to sustain the life that was already created. After further interaction amongst the spirits the valley floor parted and what was to be the keeper of life was formed. The river now flowed. The land was ready. Both man and animal descended from the spirits and moved over the earth.

They were related to each other through interactions that had taken place in the Dreaming. There was much to be learned. Laws that were made in the dreaming were passed on to man by the spirits. Man was thus made aware of these laws and passed them on to succeeding generations. Like a chain, the laws began moving across the generations. Answers to the great questions of life were there to be learned. The land held the key to life’s secrets. Man was given the knowledge to read the land and for every rock, tree and creek he found an explanation for existence.

He did not own the land, the land owned him. To know the land was to know life, for what better way of knowing life than to know the stage on which it was enacted. The land of the Wonnarua not only held human and animal life. It was the home of spirits – spirits who were born in the Dreaming. The land was full of spirits. They had their own territories localised in rocks, trees, the river and its creeks, the mountains and gullies. Playful spirits darted in and out of rock crevices and chased each other through creeks or bush and hid in the shadow of large mountains. Some spirits had a more vital purpose. Child spirits hovered, waiting for the consummating event that would change spiritual life to physical life. Something made these child-spirits scurry and a form appeared – a human form. They had known these forms, but this one was special, it was woman, the partner of man. She was receptive. The spirits knew why she came and were ready, but only one spirit would act. It happened. The woman was not aware of it. A child spirit had entered her womb, and this meant change – change from spiritual form to physical form. The child spirit had life.

The Wonnarua, like other Indigenous Nations throughout Australia, probably did not connect sexual intercourse with the birth of children. They believed that conception started when a child spirit entered the womb of the woman. A child’s birth had to be explained spiritually, not physically.

When her time came the woman went into the bush accompanied by two or three female companions. The baby was born. If a woman was carrying more than one child on the breast (abuk) then the newly born infant may well have been killed and the spirit child returned to the spirit pool. The task of infanticide was carried out by designated old women, who usually suffocated the child.

Surviving children became full spiritual and physical members of the tribe. Whether the child was male or female, its spiritual being and kinship relationships would already be known to the tribe. The child’s closest relatives were its biological parents who were naturally called mother and father. However, the mother’s brother was also called father and his children were called brother and sister. The mother’s brother was the most important person in the life of the child. It was he who guided the male child through the important steps of tribal life, leading up to initiation. He also had a great deal of responsibility for the female child. This was a common practice amongst most tribes throughout Australia. All members of the camp stood in some relation to the child.

They were his kin. This was the Koori concept of the extended family and it is not surprising that extended families are still important in contemporary Koori society. Everyone had a well-established network of identities and obligations that would last through life. Kinship welded Koori society together.

But another form of identity was vital to Koori society. Kinship explained the physical relationship between people. As well, a system of moieties, sections and totems connected the human being to his or her spiritual ancestry. Throughout Koori Australia, a complicated system of spiritual descent governed day-to-day life in the tribes. For a Wonnarua baby, descent was traced from the father.

This may well have been the case in pre-white Wonnarua kinship patterns but after the invasion into Wonnarua Lands by the white man, the spread of disease, the use and abuse and discarding of

Wonnarua women and the subsequent defeat of Wonnarua men in the battles between the gun and the spear, it was to Wonnarua women that Wonnarua society turned to for survival and this influenced me greatly and to personally follow my Wonnarua identity, through my mother’s line). The tribal members were divided into two moieties (or halves) and the newborn belonged to the father’s moiety. The mother belonged to the opposite moiety. Each moiety was further divided into two sections and the new-born belonged to the section to which the paternal grandfather belonged. These moieties had evolved in the Dreaming, a legacy of the spirits, and they remained unchanged linking ancestor to descendant through countless generations of males. However, the moiety and section system had a more practical purpose. The section system regulated marriages. This system prevented in-breeding within the kinship groups where numbers were likely to be small. Marriage was so pedestrian in Koori life that it needed no special ceremony.

This was because marriage was arranged many years before the wife went to live with her husband. She was simply expected to move into his camp when the time came. In many instances, she knew who her husband was when she was a small child. The important ceremony therefore was not the marriage but the betrothal, and this took place when the bride was only a baby. The future marriage relationship was negotiated by the guardians of the two partners. Children grew up with their life’s passage comfortably predictable. A Wonnarua camp (wattakaa) was no doubt a very busy place, with children leading a carefree and indulged lifestyle. Their playing activities were spontaneous and followed no regular pattern initially. But later both sexes played various games that involved a great deal of imitating of adult roles. Boys possessed miniature spears (durrane) boomerangs (barragan) and shields (korreil), while girls had dillybags (buakul) and coolamons (koka). Swimming, tag, sliding down muddy creek banks and hide-and-seek were just some of the activities Wonnarua children pursued. At an early age, the septum of a boy’s nose (nockra) was pierced for the insertion of a nose peg after reaching puberty.

As they grew older, more responsibility in tribal cooperation was expected of the children. Older boys were expected to accompany males on the hunt, learning and observing. Upon reaching puberty, the young adults were fully aware of some of the important laws of the tribe without fully understanding all the implications. They would have been told legends about significant aspects of their environment by storytellers. Storytelling was one of the ways that Wonnarua children were disciplined in the morals and values of their society. The stories that were told about their land began to fall into place when initiation for boys began and when girls reached puberty. Puberty was an extremely important event in the life of a Wonnarua male. It means behaving with a more serious attitude. Childhood behaviour was forsaken for the responsibilities of an adult. The signs that the boy was changing slowly became evident. It was time for him to be prepared for manhood.

He would have shared this ordeal with other boys his own age from neighbouring kinship groups, or even neighbouring peoples such as the Worimi, Awabakal, Wiradjuri or Darkingung, and much preparation had to be done. Messengers were sent to other kinship groups and peoples with the news of the forthcoming initiation ceremony. These messengers presented small white crystals to those groups invited. If they accepted, the messenger would return to his own people with another type of stone to show the acceptance of the invited group.

About four days before the actual ceremony, the invited peoples gathered in full ceremonial adornment. Each visiting group received a hearty welcome by the hosts. They made special ceremonial artefacts like durranes (spears) and barragans (boomerangs). Members of each separate group painted themselves with animal fat and made markings on their bodies with white pipe-clay and ochre. It was a time for feasting and merriment was enjoyed by all. When the event was ready, the boys were taken from their camp and prepared by their relatives or guardians, chief of whom was the mother’s brother. The ceremonial ground was the focus of this intently spiritual experience. Many initiation sites existed throughout the Hunter Valley. One in particular was situated near the Allyn River not far from the town the white man now calls Gresford. It was probably at this site that my great great-grandmother’s kinship fathers passed those intermediate days between boyhood and manhood. The kackaroo (ceremonial ground) was surrounded by carved trees and bushes. A large public circle was carved into the flat ground. From this circle, the yuppang (pathway) stretched 550 paces to the goonambang (excrement place). This latter circular area was smaller. These two circles connected by the path formed the sacred ground. After being prepared by their families, the boys were now ready to experience the transition from boyhood to manhood.They were taken from their mothers by their main guardian and walked to the kackaroo where they waited silently, pensively, for what was to come in this awesomely contrived religious ceremony which would change their lifestyles and their attitude to the land and to their spiritual being. The women and children walked to the kackaroo and were told to lie face down in the middle of the large circle.

They were covered with pieces of bark and bushes. By this time the men had commenced a steady clapping of barragans (boomerangs) or any other implement they may have had. The women started humming in a low drone. This activity was to keep them from being aware that their boys were being taken stealthily from the kackaroo to the goonambang. What was going through the minds of the initiates on this walk would have beenawe-inspiring. The mysticism of the event was incomprehensible to them at this point, and complete trust in their guardian was all they had. What the guardian said, the boombits (initiates) believed.Anxiety states were deliberately contrived by the guardians who told the boombits that the Goign (great spirit) was attacking the camp and killing the women and children.

The men at the goonambang had already been informed that the boombits were on their way. The ceremonial break from their mothers signified the first step towards man hood, it was the beginning of an event that would make them spiritually as well as physically different from women. No longer would they eat the female species of game, or collect fruits and yams or even eat with the women. At the goonambang, a fire lit the centre where a number of elders were sitting. The boombits were seated on some bushes that were placed in the inside of the ring, near the side that was nearest to their country, and told to put their heads between their knees. This position was held for some time.

As the boys took this symbolic leave of their mothers, the ceremony geared towards its climax. At the goonambang, spirit world and tribal world united in what was probably the deepest religious experience a Koori male would ever have. To signify the religious importance, the initiates were given rock crystals warmed in an open fire and told that these were the excrement of the great spirit Goign (hence the meaning of goonambang—the place of excrement). It was also here at the goonambang that the boys experienced what was to be their harshest physical ordeal of the ceremony.

It was this ordeal that tested their physical and emotional abilities almost to breaking point. At various times they were ordered to assume uncomfortable positions and to remain so until the sun crossed the sky. Climactically the upper tooth was extracted by an elder and the slightest indication of objection or pain resulted in ridicule. It is today difficult to ascertain what actually happened at the climax of the ceremony, but the spiritual experience was to be impregnated in the memories of these young boys until their final return to the spirit world. Finally the initiates were sent out into the bush, to prove their capabilities as hunters and men. They had to fend for themselves. As they departed their mothers tied some green leaves to yam sticks, and when these leaves turned brown, the mothers knew their boys would return for the final symbolic suckling of the breast. The bush provided the secular climax of the ceremony. Here a boy drew on all his previous learning to become one with the land and he was given the opportunity to demonstrate his knowledge of every animate and inanimate object.

When this experience assured him that he was a self-sufficient hunter, he returned, when the leaves turned brown, to take his rightful place amongst his people as well as the responsibility that went with this status. Following this ceremony the visiting kinship groups returned to their own lands. The kinship group was the economic and social unit of the tribe. Members were related to each other by their kinship classification, common language and law. It was the kinship group that moved within various allotted areas of Wonnarua lands in search of food, and it was only occasionally that these groups would meet to discuss important matters concerning the Wonnarua people as a whole. Such issues were considered by a council of elders, whose decisions were respectfully upheld. There was no single person such as a king or chief who could rule individually, but certain men had a much greater influence in decision-making than others. Punishment within the kinship group usually consisted of ridicule and social ostracism for minor offences such as disrespect to elders, lack of cooperation, overt greed or the unjust punishment of someone else’s child. Punishment for major offences, such as unacceptable elopement or the wilful injury of another member of the group, were dealt with more harshly. For example, the offender could be placed in a circle where boomerangs, spears and clubs were thrown at him. The spirits determined his fate, and if blood was drawn then the matter was settled.

The female offender might receive a sound thrashing from her male guardians. In extreme cases of law breaking, death was prescribed. Following a male’s initiation, he was technically of marriageable age. However, marriage throughout most of Koori Australia was delayed for the male. It was a common practice to marry young girls to much older males, and the betrothed wife of a newly initiated man might only be a toddler. This custom had the effect of a type of birth control, but it also produced a great deal of frustration for young virile males, denied a wife until some distant future. A practice common amongst the Wonnarua was that of wife raiding. A young male, impatient of waiting for his betrothed to reach puberty, would have to look outside his own kinship group for a woman whom he could take by force. Usually a wife was taken from a distant group of the Wonnarua or from a neighbouring people. The Wonnarua in their turn were raided by other peoples and they were particularly troubled by the Kamilaroi who occupied the headwaters of the Hunter River.

Wife-raiding generally entailed some form of retaliation by the guardians and the betrothed of the kidnapped woman and this was probably the greatest cause of violent hostility between various peoples in the Hunter Valley. In the more mundane aspects of Wonnarua life the quest for food consumed a significant part of the waking hours. Like all tribes in Koori Australia, the Wonnarua followed a hunting and gathering lifestyle. Each kinship group moved in a cyclical pattern through their allotted lands. Men were responsible for hunting the larger game, such as the womboin (kangaroo), murrin (emu), ukae (dingo) and the baninbellang (wallaby). Their skills were also applied to fishing. Women, on the other hand, gathered bush fruits, yams, grubs, roots, waterlilies and the many species of smaller game such as the wirraman (lizard), mouse and possum. Thus sex roles were clearly defined in the daily round. Although food supplies fluctuated with the seasons and the vagaries of nature, the diet of the Wonnarua Kooris was varied and rich in protein, as was necessary for a physically active people. The land provided everything that was needed to survive. It gave the Wonnarua Koori his implements for hunting and gathering. It provided materials for bark shelters (mia-mias). Boomerangs were fashioned from selected trees as were spears and throwing sticks (werrewies). Stone implements, such as cleavers, knives, scrapers and bondi points (sharpened stone flakes), were readily available—the patient grinding of the edge producing an effective tool.

Most furbearing animals provided skins that were used for body-covering in the cold seasons. The Wonnarua hunters combined knowledge of their environment with knowledge of animal behaviour to effectively hunt their prey. For example, when hunting the womboin (kangaroo) they burnt off the grass and, predictably, about three or four weeks later the animals returned to feed on the young grass shoots. In the early morning the men formed a circle around the unsuspecting game and gradually closed in. They confused their prey with shouts, and when the womboin tried to break the circle they were clubbed by the hunters.

Nets (kurrila) strung between trees and suitably camouflaged were also used to capture womboin. A carefully planned and executed encircling movement trapped the prey, leaving only one escape route—in the direction of the nets. A general commotion was made and the panic-stricken animals hurled themselves into the nets where they were clubbed by waiting hunters. Nets were also used for catching emu and makroo (fish). Women, girls and uninitiated boys gathered their roots, berries and smaller game in the kokas (coolamons) and buakuls (string bags). They dug for yams and other

Tap roots with their yamsticks and waded into creeks for waterlilies. In these instances an intimate knowledge of the seasonal cycle of plant life combined with a knowledge of plant localities were essential. Although the economic necessity of acquiring food consumed a large part of the day, spiritual matters remained paramount. The spirits dictated the success or failure of the hunt and determined how food resources were to be allotted. Unseen powers or forces explained sickness and death, and in the aesthetic life much artwork showed spiritual symbolism. In Wonnarua society, death was seen as another stage in the spirit cycle. The spirit gave up its physical form and returned to the spirit world. Naturally, those left behind mourned this passing and marked it with suitable ceremonies.

As befitted their status, the passing of initiated males was treated with great reverence. The body was doubled up in a squatting position with the head touching the knees. It was wrapped in ti-tree bark and tied with cords made from fibres of stringy-bark. A 60-centimetre circular hole was dug in soft soil and the body was placed in the hole sideways. Weapons of the deceased were also placed in the hole. There was much wailing and head-cutting and burning of arms. Wounds were self-inflicted by the mourners. When these wounds healed, the mourning ceased. If the deceased was a woman or male of little importance, then very little interest would be shown, apart from the disposal of the body. This then was the cycle of life in Wonnarua society. However, the cycle did not begin with birth and end in death. These events were only stages marking the transition from spiritual form to physical form and back to the spiritual. As befitted a very spiritually religious people, the spectrum of life began and ended in that invisible but very lively world of the spirit creatures.