Brown, John (1850–1930)

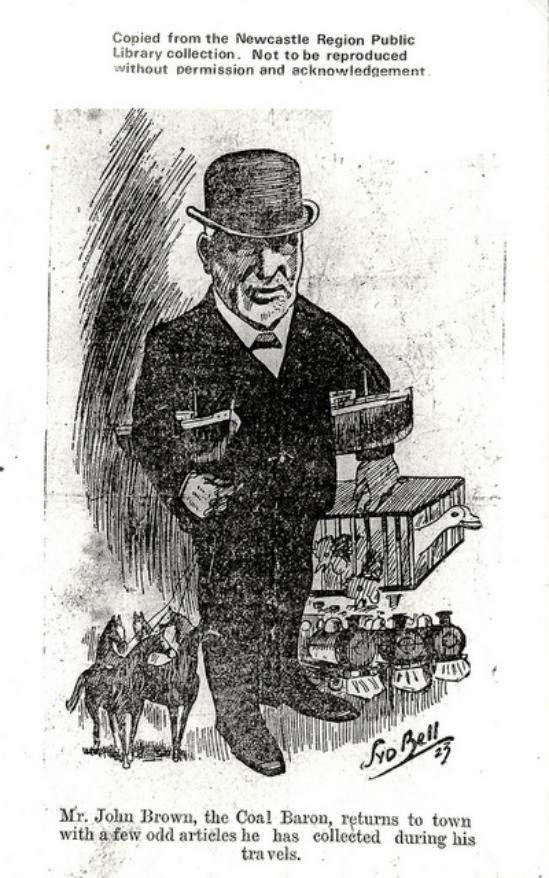

Featured Image: Acknowledge permission Newcastle Region Public Library Collection

By J. W. Turner

This article was published in Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 7, (MUP), 1979 which I duly acknowledge:

http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/brown-john-5388

Featured Image: John Brown Cartoon reproduced with kind permission and grateful acknowledgement Newcastle Regional Public Library Collection

I admit this was both stimulated and promulgated by Ian Ibbett’s excellent story:

See also: http://kingsoftheturf.com/1909-the-rebarbative-john-brown-and-prince-foote/

However there’s a lot of local ‘gossip’ still about the Browns; and also Alan Cooper. I think this was what attracted the rapt attention of Graham Harper at the Scone Men’s Shed? It also brings back into sharp focus the long history of the original Segenhoe Stud in the eponymous valley near Scone. Potter Macqueen really started something in 1824 which endures even today. Gerry Harvey and his cohort partners are the current custodians under the banner of Vinery Stud. Regrettably the name was sold when a new owner acquired a neighbouring property at Broad’s Crossing. Potter Macqueen’s ‘go to’ man was Peter Macintyre (Kayuga 1827). His direct descendent Duncan now owns the equally totemic Invermien at Scone; originally selected by Francis Little.

John Brown (1850-1930), ‘coal baron’, shipowner and racehorse breeder, was born on 21 December 1850 at Four-Mile Creek near East Maitland, New South Wales, eldest son of James Brown and his wife Elizabeth, née Foyle. He was educated at Newcastle, and at 14 began work in the Newcastle office of his father’s and uncle’s firm, J. & A. Brown. After experience underground, then as a colliery clerk, surveyor and pit-manager at the Minmi mine, he was sent overseas—to China on the firm’s business and to inspect its London agency. He also studied the latest technology and working methods in mines in Britain and the United States of America. In the 1870s he managed the Minmi mines. On 25 January 1881 at Govan, Lanarkshire, Scotland, he married Agnes Bickers Wylie with the forms of the United Presbyterian Church. However she died in Sydney on 17 August the same year.

In 1877 Brown’s uncle Alexander had died leaving his £100,000 estate to his nephews; in 1882 James appointed John general manager and handed over his coal interests to his sons in 1886. John Brown remained in control of policy. He extended the Minmi mine and benefited from membership of the Vend, a cartel which regulated prices and shared the trade between Newcastle coal-proprietors, but be left it in 1890. Free to reduce prices and with no shareholders to satisfy, he embarked on a period of trade expansion which contributed to the dissolution of the Vend and thereby helped to impoverish the district. In 1896, when many collieries were idle, his Minmi mines worked on 256 out of a possible 280 days and next year were active on 264: the firm’s annual output exceeded 300,000 tons in 1897-1901. In the early 1900s Brown expanded his South Maitland interests, acquiring the high-producing Pelaw Main and Richmond Main collieries, and by 1904 had connected both to the firm’s Minmi-Hexham railway. He also built up the fleet of tugboats which operated in both Sydney and Newcastle.

In order to develop the export trade Brown spent much time abroad and opened offices in San Francisco, Valparaiso and in London, where he mostly lived in 1888-93 and 1899-1904 while the business was managed by his brother William. William then claimed the right to participate in the firm’s management and from 1905 pursued his claim in the Equity Court. In November 1909 the partnership was dissolved by order of the court and John was appointed receiver and manager; his appeal to the Privy Council against the dissolution was dismissed.

Early in the century, Brown became famous for his horse-breeding and racing exploits. In 1893 he had begun to race horses as ‘J. Baron’, and 1897 won the Australian Jockey Club Doncaster Handicap with Superb. In 1902 he imported the stallion, Sir Foote, for his stud, Wills Gully, near Singleton. Sir Foote’s most famous son was Prince Foote: in 1909-10 he equalled Poseidon’s record in winning the A.J.C. and Victoria Racing Club Derbys and St Legers and the Melbourne Cup in the same season — as well as the A.J.C. Sires’ Produce Stakes and the three-mile Australasian Champion Stakes. That season Brown topped the winning-owners’ list with £14,610 in stakes. Duke Foote carried his pale blue colours with yellow sleeves and black cap to victory in several important races, but was the unplaced favourite in the 1912 Melbourne Cup won by William Brown’s Piastre. In 1919 John’s Richmond Main dead-heated with Artilleryman in the A.J.C. Derby and won the Victoria Derby. He bred other notable horses including Prince Viridis, Prince Charles, winner of the 1922 Sydney Cup, Leslie Wallace and Balloon King. Between 1910 and 1924 he reputedly won £90,094 in stakes. Terse with trainers, he frequently changed them, but he pampered his horses. Although by 1930 he owned 240 brood mares and seven stallions he usually refused to sell any horses even if he did not want to race them. He exhibited and imported prize dogs, poultry and turkeys, and bred stud cattle. He bought Darbalara, near Gundagai, another stud near Scone (Segenhoe), and in 1927 Dalkeith, near Gundagai, to grow maize and lucerne.

Confirmed in sole management, Brown expended much capital in his desire to be self-contained. Before World War I the firm had two-thirds of Sydney Harbour’s towing and carried out much ocean salvage work, also controlling the Newcastle pivot system until it was taken over by the government. He spent large sums on the latest mining plant, colliers, rolling stock and his Hexham shipping point and engineering works, which serviced steam and locomotive engines for other firms: on one excursion abroad he spent over £1 million on locomotives, mining equipment and a steamship to carry them home. In the 1920s he opened up the Stockrington mine and for many years he had a contract to supply the Australian Gaslight Co. In 1930 he had a large collier, 5 coastal colliers, a schooner and 10 tugs, including the Rollicker, one of the most powerful in the world — but there was little work for her. He abhorred the idea of turning his firm into a public company.

Brown’s ‘antagonism to unionism was bitterly unequivocal and even ruthless’, and ‘his passion for riding the whirlwind and defying the storm of popular disapproval’ in his relations with his miners was well known; he was also extremely reluctant to accept the State and Commonwealth arbitration systems. At Pelaw Main, from 1903 he installed modern cutting machinery manned by American technicians and free labour. In defiance of the Colliery Employees’ Federation, in 1913 he persuaded the Minmi miners’ lodge to sign a local agreement for five years. He acquired a reputation for severity, denying his Minmi miners the opportunity to buy the land on which their homes were built, and refusing to renew long leases, so they could be threatened with eviction during strikes, but he believed it was his responsibility to provide employment so long as the miners accepted the exigencies of the industry. In late 1914 he issued a writ against the Colliery Employees’ Federation for £100,000 damages for loss of trade and payment of demurrage. For much of World War I Brown was chairman of the Northern Colliery Proprietors’ Association.

In the troubled 1920s when the price of coal was depressed and the export trade dwindling, Brown closed Minmi mines (in 1922) when the men refused to accept lower wages (although allegedly he secretly arranged to pay their bills at the local store). He repeatedly warned the government that the coal trade was in jeopardy and advocated a reduction in wages. On 4 March 1929 he began ‘something in the nature of a lockout at the Richmond Main and Pelaw Main Collieries’, because he could not sell coal interstate or overseas at its current price. It was announced in the House of Representatives that he would be prosecuted; but in April the charge was dropped, to the indignation of the Labor Party which revived the question in September.

Brown died childless at his unpretentious home in Wolfe Street, Newcastle, on 5 March 1930, and was buried in the family vault in the Presbyterian cemetery, East Maitland; huge crowds watched his funeral procession. He left the residue of his personal estate, valued for probate at £640,380, and shares in J. & A. Brown to his general-manager Thomas Armstrong and to Sir Adrian Knox, as tenants in common, to carry on the firm under the same name during the lifetime of his brother Stephen.

‘Shrewd, analytical, and taciturn’, Brown shunned publicity and was an enigmatic and legendary figure, who might have stepped out of the pages of a Galsworthy novel. He was tall, spare and upright, and continued to dress ‘in sober broadcloth, glossy black boots and ties’ with a high square bowler hat. Although he was the focal point for much industrial ill-will and Labor oratory, the Australian Worker admitted that in ‘his personal relations with his employees he was by no means wholly unkind; indeed, at infrequent times, he was comparatively generous’. He had a ‘strong strain of theatricality’ and liked playing the part of the relentless capitalist. Nevertheless he made a practice of getting out among the miners.

His brother William (1862-1927) shared his interest in racing: as well as Piastre, he had other winners in Haulette, Thana and Colbert. He managed the Duckenfield colliery at Minmi for a time and was consul-general for Chile. He died unmarried at his home 153 Macquarie Street, Sydney, on 2 February 1927, leaving his estate to his brother John and sister Mary Stephen Nairn. Their youngest brother Stephen (1869-1958) was educated at Newington College, Sydney. After John’s death the firm’s interest in tugboats was sold to the Waratah Tug & Salvage Co., and from 1931 Stephen was a partner in and a director of J. & A. Brown & Abermain Seaham Collieries Ltd after its amalgamation. He travelled widely, enjoyed fishing and at Segenhoe grew prize dahlias and chrysanthemums. He died unmarried on 19 November 1958 at 153 Macquarie Street, Sydney, and left his estate, valued for probate at £149,977 to (Sir) Edward Warren.

Brown’s first cousin Alexander (1851-1926), merchant and politician, was born on 9 February 1851 at Maitland, New South Wales, son of William Brown, medical practitioner, and his wife Mary, née O’Keefe. He was educated at West Maitland, then articled to his stepfather Joseph Chambers, and admitted as a solicitor in 1873. On 8 August 1872 at West Maitland he married Mary Ellen Ribbands. He entered J. & A. Brown and, after his uncle Alexander’s death in 1877, took over the Newcastle office. In 1883, following an overseas trip, he was dismissed by his uncle James after selling the Ferndale colliery without approval. Next year he unsuccessfully claimed in two Supreme Court cases that he was a partner in the firm.

Alexander relinquished his interest in J. & A. Brown in return for his cousins’ share in the New Lambton mines, which he thereafter managed and turned into the New Lambton Land & Coal Co. Ltd in 1891. During industrial disputes he pursued an independent line from other proprietors and occasionally supported the miners. In 1885 he became manager of the Newcastle branch of Dalgety & Co. Ltd and in 1905 managing director. He also built up extensive pastoral interests.

In 1889-91 Alexander represented Newcastle in the Legislative Assembly as a Protectionist and supporter of (Sir) George Dibbs who was a director of the New Lambton Land & Coal Co. Defeated in 1891 Alexander was nominated to the Legislative Council on 30 April 1892. In 1892-96 he was first president at a difficult period of the Hunter District Water Supply and Sewerage Board at £300 a year; repeated questions were asked in the assembly about his anomalous position of holding an office under the Crown while a Member of Parliament. In 1895 a select committee investigated the cost of construction works and in 1897 there was a royal commission into the board’s management, but Brown emerged well from these inquiries. Although strongly conservative, he was regarded as ‘a fair fighter’.

Alexander was president of the Newcastle Chamber of Commerce in 1888 and 1892. He was Belgian consul in Newcastle in 1882-1926 and was appointed chevalier of the Order of Leopold in 1902; he was also consul for Italy. He died on 28 March 1926 at his home, Cumberland Hall, East Maitland, and was buried in the Presbyterian cemetery. He was survived by five sons and three daughters of his first marriage, and by his second wife Edith Mary, née Adams, a nurse whom he had married on 27 March 1920. His estate was valued for probate at £60,871.