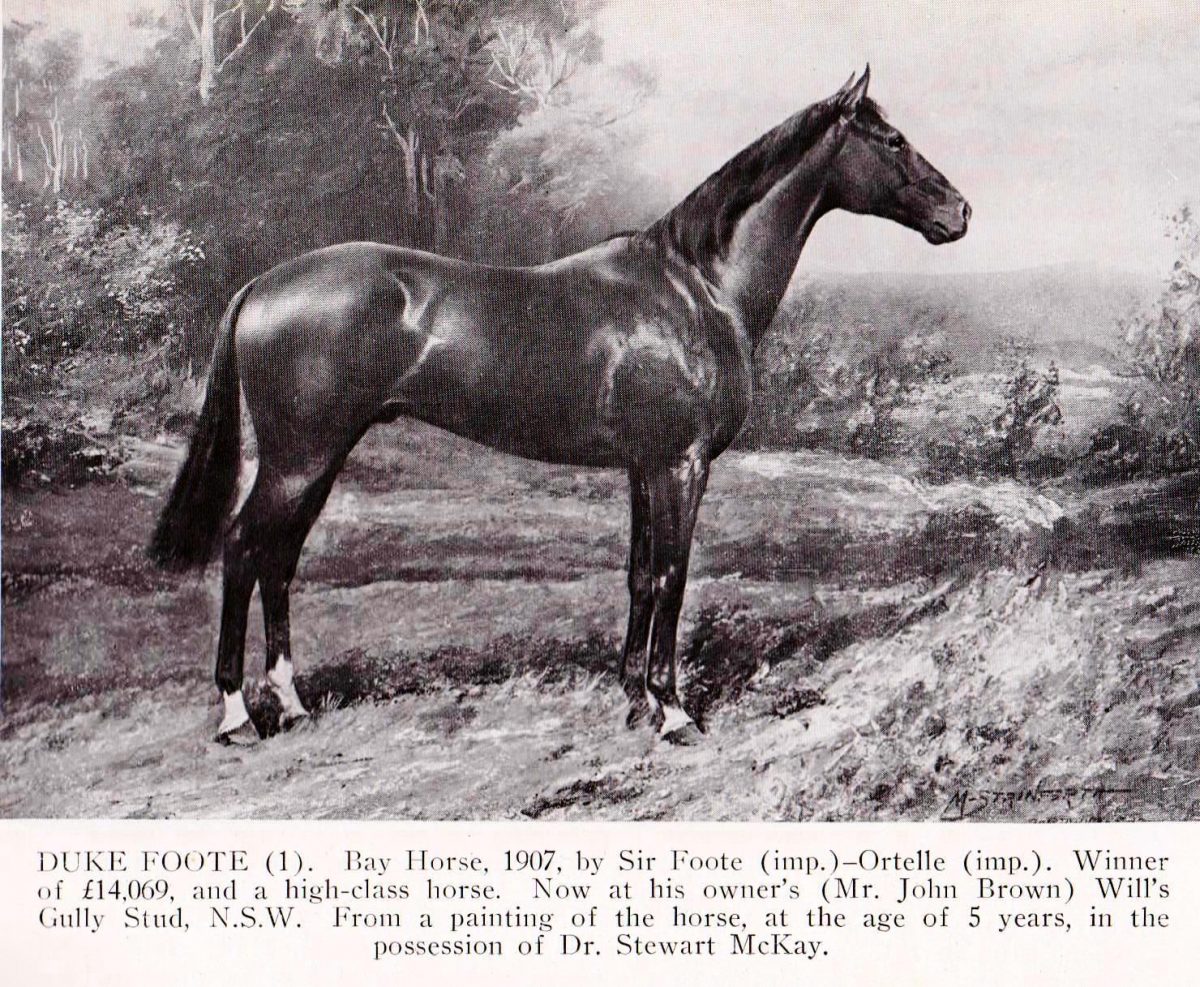

Duke Foote (1)

Bay Horse, 1907, Sir Foote (imp) – Ortelle (imp)

Featured Image from a painting of the horse aged 5 in the possession of Dr Stewart McKay

Plate in ‘Racehorses in Australia’ (Edited by Dr W H Lang, Ken Austin and Dr Stewart McKay

Duke Foote was winner of £14,069 in stakes and high class racehorse. Duke Foote stood at his owner’s (Mr John Brown) Will’s Gully Stud in NSW. Mr Brown was one of the early Newcastle ‘coal barons’ who invested heavily in the thoroughbred industry at the time. The pendulum has swung away one hundred years later. The mining and thoroughbred breeding industries are at ‘loggerheads’ in the Upper Hunter as the former expands inexorably further up the valley. It’s my personal view that the two industries can peacefully co-exist; but it’s a bad look?

There is an excellent review of the Brown Family by Ian Ibbett now available online as cited below. The full review and photographic image can be viewed by clicking on the URL.

The Rebarbative John Brown and Prince Foote! (1909)

http://kingsoftheturf.com/1909-the-rebarbative-john-brown-and-prince-foote/

By Ian Ibbett

In 1900’s

The year 1909 introduces into our chronicle one of the more colourful – if less attractive – of those dramatis personae to have owned a Derby winner. The man in question, John Brown, was born in 1850 at Four Mile Creek near Morpeth, the eldest son in the second generation of the Newcastle family coal firm of J. and A. Brown. It was a company founded by his father and uncle in the middle of the 19th century, and his childhood coincided with the move of the firm’s headquarters to Newcastle. John Brown’s uncle was the real guiding spirit of the firm in its early days. It was a privileged start in life but not one that fathered a man of charm or bonhomie with a liberal outlook. I think quite the contrary. John Brown was every inch the dour and taciturn Scot of his forebears; he shunned publicity although possessed of a strong element of theatricality and he seemed to relish the role of relentless capitalist. Tall and lean, he cut a conspicuous figure on the racecourse as he continued to dress in sober broadcloth, gleaming black boots and tie, topped off by a high square bowler hat, long after the fashion had ended. With his thinning silver hair and a moustache that flourished into a close-cropped beard in his later years, he might have stepped straight from the pages of a John Galsworthy novel. And this man of property seemed to personify the very worst features of Soames Forsythe in those heady days of rampant capitalism that marked the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth.

It was the family coal firm that was to provide the immense sums of money that Brown poured into horse racing from around 1893 until his death in 1930. The firm was already a thriving concern when he became general manager at just the age of thirty-two, but under his shrewd stewardship, he steered its fortunes to ever more prosperous levels. It became an empire of extensive collieries in the Hunter Valley with its own rail link, locomotives and workshops, besides boasting an extensive fleet of tugboats that dominated Sydney and Newcastle harbours. Obsessed with power, over the years John Brown cultivated both State and Federal politicians, and it was his extensive interests in racehorses that often provided him with the smoothest access to the political class. Nonetheless, Brown’s autocratic and ruthless personality earned him considerable enmity not just from the unions and other coal mine owners, but his own family as well.

His own brother, William, took him through the courts in a bid to establish a right to participate in the management of the firm, which was eventually acknowledged, but not before the challenge had gone all the way to the Privy Council. The partnership eventually dissolved although ultimately John was to emerge the real manager. Such spats of fraternal bitterness were nothing to the acerbic nature of his relations with his miners and towards the concept of trade unionism in general. He denied his own miners the opportunity to buy the land on which their homes were built, even refusing to renew long-term leases, thereby retaining the power to threaten eviction during strikes. Brown shunned publicity and hated cant or hypocrisy, and he could be as blunt as circumstances warranted. He travelled the world to find customers and organise agencies for his coal; agents of the firm were in the shipping quarters of most of the big cities in the world. The result was a great demand for Newcastle coal by steamers using the Seven Seas. As a young man John Brown had married, but tragically his wife died on one of his early visits to the Old Country. Brown took the loss rather badly, and one can only speculate to what extent this misfortune deepened his misanthropic nature. He never married again and in a curious pattern of behaviour that might have come straight from the quill of Dickens, demanded that his housekeeper maintain his wife’s room as she had left it with her clothes to be regularly aired.

Perhaps virtue does enjoy its own rewards, and vice incurs its own punishments, but I have never found that it is the place of the racecourse to meter out such consequences. It was John Brown’s good fortune to see his colours carried to victory in the A.J.C. Derby not once but twice and the first occasion came in 1909. From the time that he amassed his first million, Brown became known as ‘The Baron’; it was a title that he relished and when it came to registering ownership of his horses he used the nom de course of ‘J. Baron’. However, it wasn’t until 1897 that he enjoyed his first major success when he won the Doncaster Handicap with the gelding, Superb. Brown travelled abroad extensively on business, spending much time in England and it was while living there in 1901 that he negotiated the purchase of the stallion, Sir Foote, for his stud Wills Gully, near Singleton, NSW. It was this horse that was to lay the foundation of Brown’s greatest triumphs on the Turf. Sir Foote had raced in England, and though his conformation and brilliance were impressive, he was but little prized in the Old Country because of a history of unsoundness. It was this that enabled Brown to get him at a selling plate price.

Brown reasoned that even if the horse couldn’t stand a preparation on the hard tracks in Australia, his bloodlines and conformation made him a likely stallion prospect. After all, his near full brother, Surefoot, had won both The Two Thousand Guineas and the Eclipse Stakes in England and had even started an odds-on favourite in The English Derby of 1893, only for temperament to get the better and relegate him to fourth place in the race won by Sainfoin. But whereas Surefoot was a savage devil, Sir Foote was most equably tempered. Up to that time, Brown had already imported some useful stallions such as Trussing Cup, Jolly Hampton and Simile into Australia, but Sir Foote was to prove his real find. When the horse landed in Sydney, he was almost lame as he hobbled off the boat, and while resting at Windsor Farm, it was all he could do to shuffle about in the sand yard. But Ike Earnshaw, who was Brown’s trainer at the time, was a remarkably patient man and eventually got Sir Foote ready for racing. Though the horse was always half-crippled, Earnshaw managed to fit him up well enough in the autumn of 1902 to win the Newmarket Handicap at Flemington and the Futurity Stakes at Caulfield before coming to Randwick and taking out the Doncaster.

Though Brown owned many horses before the advent of Sir Foote, he didn’t breed on a large scale until that stallion’s retirement. When Sir Foote got that smart colt, Antonius, in his first crop it seemed that his stud reputation was assured, but unfortunately, he died all too soon afterwards. A first-class show horse usually kept in peak condition, Sir Foote was found dead in his stall from peritonitis shortly after returning to Motto Farm from the Royal Agricultural Society Exhibition at Moore Park at Easter 1907. However, in the spring prior Sir Foote’s death, one of the mares roaming the Will’s Gully paddocks had dropped a tiny bay colt by the stallion. The little fellow was destined to bring posthumous glory to his sire’s name and become the finest racehorse ever to sport the colours of John Brown on the Turf. The mare in question, Petruschka, was one of those finely-bred English mares that the Baron was in the habit of buying on his European travels and shipping back to the Hunter Valley.

A daughter of the great racehorse Isinglass, winner of the English Triple Crown in 1893, out of a good race mare that had won six races in the Old Country, Petruschka had never been tried on the racecourse herself. She had come to Australia in 1903 along with her dam, only two years after Sir Foote. She had cost quite a bit of money to land here, and when her first two foals failed to make their mark, Petruschka began to look distinctly expensive. It was to be third time lucky, however, when she was mated with Sir Foote in that spring of 1905 for the resultant foal was to be the little claret-bay colt, Prince Foote. Reared at John Brown’s property at Warrah – then one of the most fertile patches of pasture on the Liverpool Plains – when it came time for the colt to be broken in and prepared for a life on the Turf, he went into the Randwick stables of Frank McGrath. McGrath was then 44-years-old, and the fires of his determination had already begun to forge the reputation that would see him acknowledged as one of the great Australian trainers of the century. In Prince Foote, he got a colt worthy of his steel.

As we have seen, McGrath had already won the Derby with Abundance in 1902 and enjoyed other successes that same year in the Toorak Handicap and Villiers Stakes with his own horse Kinglock. The next decent galloper that the Master of Stormy Lodge got his hands on was Little Toy, a son of Positano, which he raced himself. McGrath bought the colt through the sales conducted by Thomas Clibborn for just 85 guineas only three days after Abundance had won the A.J.C. St Leger. Curiously enough, Little Toy was bred by Richard H. Dangar at Neotsfield from a mare that his father, Henry C. Dangar, had imported from England. Given the significance that another branch of the Dangar family was to play in Frank McGrath’s eventful life, it is an interesting sidelight of history.

In just one victory – that of the 1906 Doncaster Handicap – Little Toy did more than virtually any other racehorse to guarantee the prosperity of Frank McGrath and his family. Unraced at two and sparingly raced at three, Little Toy was set for the Doncaster as a four-year-old getting into the handicap with just seven stone. A few weeks before the race, McGrath confided to fellow Randwick trainer and good friend, Tom Scully, that he fancied the son of Positano for the big mile, and in turn, Scully admitted that he liked one of his own, Noreen, for the Sydney Cup. McGrath coupled both horses in doubles at lucrative odds, and when Scully’s boast made good, Frank McGrath became a wealthy man overnight. Little Toy lived up to his part of the bargain in devastating style. In the hands of Andrew Thomas, who was then an apprentice with Alfred Foley, Little Toy at 8/1 streeted the field to win by five lengths. Out of the proceeds, McGrath proceeded to build four contiguous cottages in Kensington-avenue on land adjoining his stables.

Despite being a son of Positano, Little Toy wasn’t a big horse, and his Doncaster victory lifted him in handicaps such that he failed to win another race of any significance. Nonetheless, it was a happy reminder to Frank McGrath that good things come in small packages; after all, McGrath was a man who first made his name training ponies. Now another good little ‘un had arrived on his doorstep. If McGrath was disappointed with the pint-sized Prince Foote the first time he set eyes on him, he never let on; and McGrath was more than elated the first time he set his stopwatch on the little colt. Never a man to rush his juveniles, McGrath delayed the colt’s debut until early autumn and a four-furlong scamper at Moorefield in which he went around unnoticed. Given the educational value of that outing, the stable supported Prince Foote at his next assignment against a big field of juveniles in a five-furlong Nursery at Rosehill. The colt had only 6 st. 10lb and McGrath had engaged a promising young apprentice by the name of Jim Pike for the ride. The inexperience of both horse and rider showed at the start, and after being awkwardly placed, Prince Foote came with a powerful finish inside the distance to be just beaten into third placing – less than three-quarters of a length from the winner. The McGrath stable might have left their money in the bookmakers’ satchels, but the run had topped the colt off nicely for his assault a fortnight later on the Sires’ Produce Stakes.

The talking horse in the Sires’ that year was the local Wallace colt, Sunny South, a homebred trained by Richard O’Connor at Kogarah. Taken to Victoria for the autumn meeting he had won the Ascot Vale Stakes most impressively and the Tattersall’s men, as a result, looked upon the Sires’ as a shutout with at least tens on offer about anything else. The race was being run over the seven-furlong course at Randwick for the first time, and McGrath rather fancied his colt at the extended trip. While Sunny South bowled along in front for five furlongs he was gone at the six when Malt King took him on, and no sooner did this son of Maltster look the winner than Prince Foote swept past him majestically in the final furlong to win in a very quick time. Two days and a ten-pound penalty later, Prince Foote was denied the rich Randwick autumn double at his final appearance that season when Malt King had four lengths to spare over him at the end of the shorter Champagne Stakes. But never mind the winner, from the perspective of the spring, Prince Foote’s powerful finish that day had blue riband written all over it. Badly away at the start, in the words of William Cook (‘Terlinga’ of The Australasian), Prince Foote “was lengths behind entering the straight and ran past all but Malt King from the Leger stand as if they were hobbled.”

Although Prince Foote wintered exceptionally well and strengthened considerably, he failed to grow much during his lay-off. The colt’s seasonal re-appearance came in the Chelmsford Stakes at the Tattersall’s Club Meeting in early September. Malt King and Patronatus, putatively Prince Foote’s main challengers for Derby honours, resumed in the same race and rather surprisingly were preferred in the betting in a field that included older horses the likes of Linacre and Mountain King. Prince Foote made light of his seven-pound penalty to win rather easily, although Malt King in finishing third did suffer from interference. Until the Tattersall’s fixture, a good many colts had been left in the Derby tentatively in the hope that the crack juveniles of the autumn might fail to strike form in the spring. Such wishful thinking, not unusual in owners, quickly dissipated in the light of Prince Foote’s powerful performance and the ranks of Derby acceptors thinned considerably.

*************************

The 1909 A.J.C. Derby field and race conditions appear in the table below:

When Derby Day dawned three weeks later, a field of eleven accepted for the race, with Prince Foote, the outstanding contender on paper. Next fancied in the betting was Malt King, who was the most imposing physical specimen in the race, standing head and shoulders over Prince Foote and like most Maltsters, raced big and lusty. Bred at the Widden Stud he hailed from one of the best Australian families, his dam Patrona being a full sister to the Melbourne Cup winner, Patron, and the Sydney Cup winner, Patroness, as well as the good horses, Patronage and Ruenalf. The maternal pedigree ran all the way back to Omen, one of those famous importations of Hurtle Fisher. Trained privately by his owner Joe O’Brien away from Randwick, Malt King, already the winner of the Champagne Stakes at two had followed his minor placing in the Chelmsford Stakes with an easy victory in the Spring Stakes at Rosehill just the week before. Although his speed was proven, his stamina was not, and many thought him better placed up to a mile.

An exciting runner was the New Zealand representative, Provocation, a half-brother to the New Zealand Derby winner, Elevation, owned by the Wairarapa pioneer and studmaster, W. E. Bidwell. From a most distinguished family, Provocation had been a smart juvenile in New Zealand and was the winner of the Champagne Stakes at Canterbury. Danilo, a well-bred son of True Blue, trained by Jack Mayo, represented the theatrical magnate, J. C. Williamson, in the Derby. Also included in the field were two good fillies in Lady San and Byplay, the latter trained by Ike Earnshaw and the winner of the Easter Stakes at the autumn fixture and the Spring Handicap in fast time at the recent Tattersall’s gathering. Although the Derby would prove too rich for the pair, later that spring they would quinella the Oaks Stakes at Flemington.

The weather was anything but pleasant with a strong, blustering, westerly gale bringing clouds of dust from Cleveland-street and Randwick road across the course, leading citizens to ask why, given the occasion, the City and Randwick Councils couldn’t lightly water the respective thoroughfares. It wasn’t enough, however, to deter a large crowd from attendance. Since the last Spring Meeting, the Tramway Department had constructed two additional lines of rails and a corresponding number of platforms to ease the Randwick congestion, while the cross line from Bunnerong road via Victoria Park racecourse to Botany road opened direct communication with the western suburbs for the first time. Of course, not everybody relied on public transport and some in attendance such as the Governor-General, Lord Dudley, and the State Governor, Lord Chelmsford and their parties, travelled to the course in more elegant style.

Prince Foote opened in course betting at 7/4, but as the colourful cavalcade belatedly picked its way to the start – each of the jockeys, bar Barden, was fined for being late out – money continued to tumble onto the favourite despite the shortened odds. Although the field went off at a steady pace, there was much pulling and fighting over the first half-mile. At the time McCarthy had Prince Foote on the rails and close-up behind the leaders. Provocation fighting hard with Grist next made the running, but six furlongs from home Provocation began to tire and fell back upon Prince Foote, forcing him back to last but two. The favourite quickly came again only to receive another check and at the bend remained near the rear of the field. At the entrance to the straight Patronatus, Danilo and Malt King seemed to have the race at their mercy, but once McCarthy pulled out wide on the son of Sir Foote and gave the little colt his head, it was a matter of shut the gate. In an electrifying final quarter-mile, Prince Foote won easing up by one-and-a-half lengths from Patronatus with Danilo filling the minor placing. For the second year in succession the Maitland sportsman, Joe Brown, had suffered the pangs of seeing his colours relegated to second in the classic.

John Brown elected not to start his colt again at the meeting but requested that McGrath spirit him to Caulfield immediately with the Guineas as his next mission seven days later. In winning the Caulfield race over the shorter trip, Malt King extracted a measure of revenge, although Prince Foote was his own worst enemy in missing the jump and then trying to run off the course on top of the hill. The fact that he beat all but Malt King after spotting the leaders almost a furlong, made the Victoria Derby at Flemington seem a foregone conclusion. It was. Despite the inconvenience of a split hoof that the veterinarian Sam Wood needed to rivet together about a fortnight before the race, Prince Foote won his second blue riband by six lengths. Lord Foote, a stablemate also owned by John Brown, made much of the running in that Derby and yet still managed to hang onto third placing, a head behind Danilo. It was a memorable day for trainer Frank McGrath, for his filly Desert Rose took out the Maribyrnong Plate earlier in the day. Such was Prince Foote’s dominance in the classic that he was immediately installed as favourite for the Melbourne Cup, just ahead of the great Trafalgar, which that year was having his first start in Australia’s richest handicap.

Prince Foote thrived in Melbourne once the split hoof mended and McGrath regarded him as a good thing for the Cup with 7 st. 8lb or two pounds over weight-for-age, provided the little fellow avoided interference. With McCarthy unable to do the weight the job of steerage fell to the 22-year-old ‘Midget’ McLachlan. Second-last in the field of twenty-six going down the riverside after earlier interference, he steadily improved his position but coming around the home turn was still fully three lengths or more adrift of the heavyweights Alawa and Trafalgar. McLachlan had only ridden the colt once before in a track gallop and never in a race; he was wholly unprepared for the acceleration that came with just one crack of the whip and was still marvelling at it thirty years later when he told his life story. McLachlan came to regard Prince Foote as the best racehorse he ever rode in Australia in his long career but ruefully recalled that he got no more than his riding fee and the statutory percentage from Brown for landing the Cup. The crusty and querulous old autocrat was a little more generous to the V.R.C. committee when he presented them a silver-mounted hoof of Sir Foote, in the shape of an inkstand a few weeks later to celebrate his Flemington triumphs.

When Prince Foote resumed racing in the autumn, he remained just as dominant, winning both St Legers in hollow fashion, as well as trumping the older horses at weight-for-age in the Champion Stakes at Flemington and the Cumberland Stakes at Randwick and leading all the way in the A.J.C. Plate in very fast time. In fact, his only defeat during that campaign came when Malt King beat him in the All-Aged Stakes at Flemington over the mile. I might add that the three-mile Champion Stakes, moved from the midsummer programme to the autumn, was something of a farce that year when neither Prince Foote nor his two rivals wanted to make the pace. The result was that the winner took 8 minutes 47 seconds and given that it exceeded the time limit, John Brown forfeited half the prize. Not that it mattered much in the overall scheme of things, because, thanks to the dominance of Prince Foote, John Brown topped the Winning Owners’ List for the season with £14,610 in stakes – a new record for an owner eclipsing the previous record set by the J. B. Clark syndicate in 1893. It was one of the great three-year-old seasons of all time, very similar to Poseidon’s and was to be the high-water mark of John Brown’s life on the Turf.

Prince Foote began his four-year-old season in the same manner as the year before – with a convincing victory in the Chelmsford Stakes – only this time humping 9 st. 7lb, and it seemed that past glories would be repeated. It wasn’t to be. Sent out at twos on at his next appearance in the Spring Stakes, the imported Comedy King was untroubled to cause a boilover in relegating him to second place. When Prince Foote then finished unplaced in the Craven Plate won by Parsee, McGrath abandoned the entire campaign, and the horse went to the spelling paddock for almost a year. Then for the third year in succession, his seasonal re-appearance came in the Chelmsford Stakes, but dreams of a hat-trick were soured when he failed ignominiously. It was the same story in three more appearances at weight-for-age during the Randwick Spring Meeting.

It was after the last of these – in the two-mile Randwick Plate – that Prince Foote bled and his racecourse retirement was announced. The stallion went to stand duty at his owner’s Wills Gully Stud, among the hills and dales of the Hunter Valley, a few miles from the Rothbury Ranges.

Brown exercised the jealous right of exclusive property with all of his stallions, and Prince Foote was to suffer from this parsimony. Nonetheless, he proved himself a very able stallion, siring some first-class horses, most of which carried John Brown’s pale blue and yellow livery. It is a curious fact, however, that all of Prince Foote’s best progeny were colts. As we shall see, he was responsible for Brown’s second success in the A.J.C. Derby with that fine chestnut colt Richmond Main, and his younger brother Pelaw Main which won the A.J.C. December Stakes. Prince Foote’s other good winners for John Brown included the dual St Leger winner, Prince Viridis and the 1922 Sydney Cup winner, Prince Charles. Prince Cox (V.R.C. Australian Cup) and Prince Minimbah (A.J.C. Summer Cup) were among other notable progeny by the Derby winner. Prince Foote died at the Wills Gully Stud in January 1922 from a ruptured blood vessel.

In the autumn of 1930, at a time when even the great Amounis was stabled in Stormy Lodge and enjoying his finest season, Frank McGrath looked back on his racing career in an interview with Jack Dexter. McGrath reflected that up to that time Prince Foote, a wonderfully clean-winded horse, was the best he had ever trained. While it was an opinion that McGrath was to review less than three years later when a certain showy chestnut with a flaxen mane and tail walked into his life, the later revision doesn’t necessarily detract from his initial judgement. The great man admitted that he never galloped Prince Foote beyond nine furlongs when preparing him for his longer races and these were training methods that at the time drew criticism. He recalled that some wiseacres had buttonholed John Brown before the Derby at Randwick and told him it was impossible for Prince Foote to stay on such a light preparation. Brown had reported the doomsayers’ advice to McGrath, whose laconic reply was: “When he’s tired, I don’t know how the others will be.”

Prince Foote was easily the best horse that John Brown ever raced in his long career on the Turf, although the next best was arguably another son of Sir Foote in Duke Foote, winner of an A.J.C. Metropolitan, two Craven Plates and some other top-class weight-for-age events. He was the horse that triggered one of the most hostile demonstrations ever witnessed at Randwick. It came at the 1913 A.J.C. Spring Meeting and the incident distils the essence of John Brown’s character.

Duke Foote was a hot favourite for The Metropolitan that year and had been the subject of much pre-post betting, but was scratched a few days before the race. There was nothing wrong with the horse, however, and when Duke Foote proceeded to win the Spring Stakes on the first day of the meeting, elements in the irate crowd loudly hooted the presentation. Just as the demonstration was subsiding and the attendant was leading the horse away, John Brown stepped forward and ordered the horse to be brought back. He then proceeded to pat Duke Foote on the neck, and all hell broke loose yet again. When the demonstration was at its height, Brown with characteristic hauteur stepped forward to face the crowd, smiled, bowed, and raised his hat. He remarked afterwards: “The public can rely upon every horse I run being a genuine trier, but I will not allow them to dictate to me as to which races I will run my horses in.” As he was doffing his hat, an enterprising news photographer snapped the image, and it appeared in all the papers. John Brown was so impressed with the photograph that he obtained an enlargement and had it framed and hung on the wall of his home on the hill in Woolf Street, Newcastle, where it remained for years.

Duke Foote was also the horse that was again to bring John Brown into direct conflict with his younger brother, William, although this time on the Turf itself. The occasion was the 1912 Melbourne Cup in which Duke Foote started as a hot favourite to land the prize but finished unplaced behind Piastre. The latter just happened to be owned by William Brown and at Flemington on that first Tuesday in November the older brother didn’t seem to derive much fraternal satisfaction from the result. While William was to win just as many good races on the Australian Turf as his brother John, the two men could hardly have been more different characters. William was shy and retiring and something of a hypochondriac, although he did plunge rather heavily on his own horses when he first came into the game. Originally the brothers shared the common stud property at Motto Farm where they bred and trained in private with Mark Thompson in charge of affairs for a time, but there inevitably came a parting of the ways.

John established Wills Gully (a property formerly bought originally by their father) as his own stud; and William spent large sums in the purchase of bloodstock for his Segenhoe Stud, which he acquired in January 1913. It was William Brown who was responsible for bringing Multiform to Australia, and in 1911 replaced him with Tressady. Like his brother, William also imported a number of mares from England, including the remarkable Chand Bee Bee in the early 1890’s and raced her. She proved a most wonderful and versatile matron when eventually retired to stud producing for William Brown the winners Chantress (Newmarket Handicap), Bee Bee (Maribyrnong Plate), Baw Bee (Breeders Plate and Summer Cup), and Piastre (Melbourne Cup).

John Brown conducted his racing empire along the same lines as his business empire: nothing was to be done by halves; he brooked no outside interference, and his word to his employees was to be taken as a command to be obeyed. Brown conducted two thoroughbred studs, the main one at Wills Gully, Singleton, and the other at Darbarlara, Gundagai, and he derived great pleasure from his occasional visits to these holdings in the company of his select friends. There were hundreds of horses running loose at these properties and although he only ever raced a fraction of them, rarely did he sell any. In fact, many were never broken-in at all. He was determined not to run the risk of being defeated by a horse of his own breeding in the ownership of someone else.

Frank Marsden, when he was Brown’s trainer, often toured the paddocks to select likely prospects and some were four or five-year-olds before they felt the touch of a man. On one occasion, Marsden brought back a real brumby, which he eventually broke-in and registered as Prince Sandy. Prince Sandy was a five-year-old before he ever raced but managed to run second in The Metropolitan of 1921 and was the horse that H.R.H. The Prince of Wales rode on the famous occasion he turned up at early morning trackwork at Randwick. I think the only man that got the occasional concession from Brown was Bob Skelton; he managed to race some horses of John Brown’s breeding on the old pony courses. As such they didn’t represent a threat to Brown because they were ineligible to be raced on registered tracks. Skelton was known as ‘Baron Junior’.

Despite the vast numbers of yearlings that he bred himself, there were some famous occasions when John Brown patronised the sales ring. The achievements of the brothers Windbag and Bicolor were responsible for him paying 4000 guineas for their yearling brother at the Sydney Easter Sales in 1928. Registered as Magnifico and placed in Frank McGrath’s stables, the horse proved to be a roarer and never won a race. The following Easter Brown saddled up again, this time paying 2600 guineas for what he believed was a half-brother to the A.J.C. Derby winner, Prince Humphrey, by Valais. As it transpired, the colt wasn’t a half-brother to the Derby winner at all, a fact revealed just a few months later; registered as Royal Status, he failed to win in three seasons.

It was with his various trainers that John Brown’s ineffable charm was most evident. Frank McGrath was just one of many to train Brown’s horses over the years, and, although on and off, he lasted longer than most. Ike Earnshaw was the first and along with McGrath came the likes of Stan Lamond, Albert Wood, James Barden, Frank Marsden, Ike Andrews and Joe Burton. The Baron argued with them all and changing trainers seemed to be as much of a hobby with him as the actual racing of horses. He sacked Joe Burton because old Joe had the temerity to tell him that one of them wasn’t much good. Brown’s most famous split, however, involved the parting of the ways with Frank Marsden, the man who trained Brown’s second Derby winner, Richmond Main.

Marsden was arguably the most successful of all Brown’s trainers, and apart from a Derby with Richmond Main, had also won the Sydney Cup with Prince Charles for the owner; in just over three years Marsden won the Baron some £36,000 in stakes alone. Despite such success, Marsden got his marching orders, and it came in somewhat unusual circumstances. The cause of the split was the racehorse, Prince Cox, who, in Brown’s colours and Marsden’s stable was at first mediocre. It was only after the horse was sold to Sir Samuel Hordern and Fred Smith, other clients of Marsden, that the horse began to show promise, eventually winning the Australian Cup in 1923. Brown was in England at the time, but he quickly fired off a cable to his agent, John Grisdale, with instructions to remove all his horses and gear from Bowral Street and place them in the care of Stan Lamond. Sooner or later Brown would argue with most people with whom he came into contact. An exception was Sir Adrian Knox, who, when the chairman of the A.J.C. extended the freedom of the committee rooms to the Baron, a concession of which he took full advantage even to the extent of entertaining his own cronies there. Not all members of the committee were as enamoured of Brown as Knox. Brown continued to abuse the privilege even after Knox resigned from the committee to go to the High Court. As a result, Harry Chisholm broached the subject in his most diplomatic manner, but Brown took umbrage, stormed out and never forgave the club.

John Brown died in March 1930 at the age of seventy-nine in his unpretentious home in Newcastle, leaving a personal estate valued for probate at £640,380. Brown left shares in J. and A. Brown to his general manager Thomas Armstrong and Sir Adrian Knox as tenants in common, to carry on the firm under the same name during the lifetime of his brother, Stephen. It is worth remarking that in true Scots’ fashion despite their differences at times, brother William had bequeathed his estate to John when he pre-deceased him in 1927. At the time of his death, John Brown owned well over two hundred broodmares. The subsequent disbandment of his stud and stable for quite modest prices was an event that scarcely brought much regret to the Australian breeding industry, although Brown’s death wasn’t quite the end of the line insofar as Brown money expended on Turf affairs was concerned. As we shall see in the course of this narrative, quite a bit of that fortune was to be squandered – in a manner quite uncharacteristic of the Scots – during the ‘thirties through the misadventures of the hapless Allan Cooper.