Good Old Days on Cooplacurripa

See: https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/159581626

See also: https://www.phototimetunnel.com/in-the-tracks-of-tom-pritchell-bush-horseman

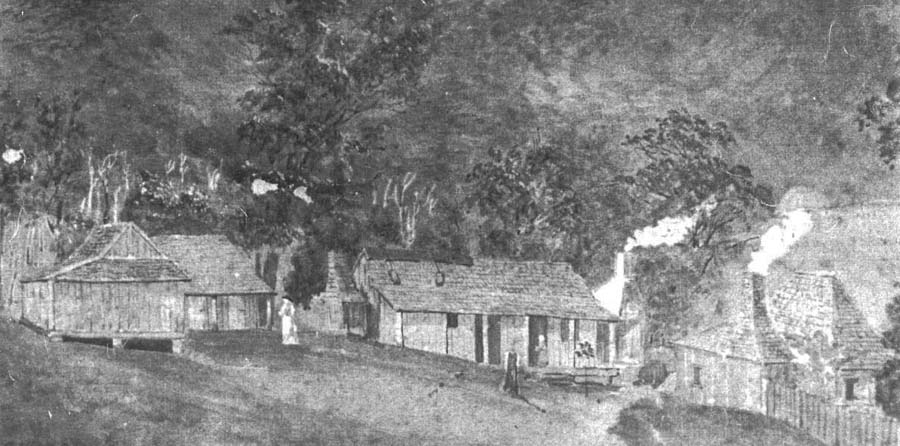

Featured Image: ‘Old’ Cooplacurripa believed to be Cooplacurripa homestead in the mid-1800s

A PEEP INTO THE PAST: GOOD OLD DAYS ON COOPLACURRIPA.

GOOD ALL-ROUND HORSEMEN AND ROUGH RIDERS.

Written ‘The Wingham Chronicle.’

BY RICHARD HINTON.

ARTICLE NO. 4.

I was about eleven years of age when I first went to Cooplacurripa Station. I was born at Cooplacurripa, and my father— the late James Hinton— was stockman, horse breaker, and blacksmith on Cooplacurripa for years before I was old enough to play a part m station work and station life.

HIRED BY J. K. MACKAY.

I was hired by Mr. J. K. Mackay, and he had a share in Giro Station. When on one occasion I was sent over to Giro Station, there was mustering work being carried out at the time at Glenrock, and I was instructed to go there. I met some of the crack riders of the day at Glenrock.

THREE GREAT HORSEMEN.

There were three dark fellows there. They were Jimmy Doyle, Jack Cook, and Albert Widders. These three men were great horsemen. Jack Cook was out on his own for breaking in horses and as an ‘all round’ horseman. Albert Widders was the best man I ever saw in a yard drafting wild cattle on foot. I have seen wild cattle charge straight at him. Albert would just step neatly aside, and the wild beasts would pass on. Under similar circumstances most other men would have been on the top of the fence.

Alec. Campbell was Boss on Glenrock Station at the time to which I am now referring. Billy Bristo was the head stockman on the same station.

‘TUGLO.’

On one occasion I remember we went from Glenrock Station to what was known as ‘Tuglo.’ This place is part and parcel of the Station property.We camped at ‘Tuglo’ for the night.

When morning dawned, we went to look for our horses. I did not bother taking a bridle with me. I could see a grey horse up on the ridge, and I thought it was mine. When I got up to the animal, I dis covered it was not mine. I did not bother going back for a bridle. I got on the tracks of the two horses I was looking for and followed them down the creek for about two miles. They were making towards Giro. I eventually overtook the two horses, put the hopple straps round one fellow’s neck, and the other one followed me. As I was returning up the’ river again to where we had camped the previous night, a mob of wild horses happened along. Some of the Glenrock chaps had started them when they were after their horses. My horse caught sight of the wild mob, and he set out after them at full gallop, 1 only had the hobble strap round his neck, and no saddle on.

‘STUCK HIM.’

I stuck him going down into a steep gully. He jumped over the gully, and was cutting out the pace in fine style going round a steep sidling. I thought it about time to leave him, and I seized a favourable opportunity and threw myself off. I rolled about 25 yards down the hill before I struck a tree. However, I was not seriously hurt.

The two horses caught up with the wild ones and went on with them. When I returned to the camp, I told Mr. Campbell what had happened. He sent two men after the horses. They got them on a high top, and the wild horses kept the two station horses away from them. The two station horses were duly caught and brought back to camp. One of them had been ‘bit’ about a little by the wild horses.

HAPPIEST AND JOLLIEST.

Some of the happiest and jolliest stockmen I ever’ met I was brought into contact with at Glenrock in my young days. There were many smart horsemen amongst them— men who could hold their own with the best men that ever hopped into a saddle.

OUTLAW FROM MUSWELLBROOK.

When I was at Glenrock, Mr. Alec Campbell bought an outlaw horse at Muswellbrook. He brought him over to Glenrock Station, and wanted some of his men to ride the outlaw? None of them showed any burning desire to mount the animal. Jack Cook, who was in the employ of Mr. Augustus Hooke at Curricabahk, was at Glenrock Station at the time. Cook was helping them to muster at Glenrock. Mr. Campbell said to ‘Cook: ‘What about you having a seat on him, Jack?’ Cook replied: ‘No, Boss. I’ll buy him from you.’ So Campbell finished up by selling the outlaw to Cook for the same money he had paid for him at Muswellbrook.

Cook took the outlaw over to the blacksmith’s shop and shod him. I helped to hold him whilst this was being done. After he had been shod, Jack Cook saddled the outlaw, and mounted him. He took him over into a little paddock near the homestead before he got on him. He was a very hard horse to get on. He used to rear straight in the air as soon as Jack put his foot into the stirrup. Jack managed to get into the saddle anyhow. The outlaw wheeled round, and bucked clean over the fence without touching it. From there he bucked down over a steep bank into the creek. He then bucked down the bed of the creek, in the water. He struck a rock while bucking in the creek, and the result was that the girths broke.

There were quite a number of station hands watching the exhibition of horsemanship. We sang out to Cook that his girths were broken. Cook jumped off. As soon as he did so, the saddle slipped round on the outlaw, and he gave it one kick and sent it flying yards up along the bank of the creek.

Cook still held the bridle and stuck to the outlaw. He brought him up into the same paddock again and saddled him once more. He then hopped on to him. This time the outlaw bucked over the fence on the opposite side to that he had cleared in the first instance. It was a two-rail fence. Cook had the best of the outlaw, and the outlaw never touched it. Shortly after and rode him to a standstill. He was the only man who ever did so.

Cook had this outlaw for years. He could ride him all right, but no one else ever succeeded in sticking him. Cook sold the horse at various times to different people— on trial—but every time he got him back— none of them could ‘sit’ him.

HORSEMEN I HAVE KNOWN.

I have ridden with many rough riders in my younger days, but I would say that the late Duncan McPherson and W-. H. Mackay were out on their own— that is to say, as real rough riders. They did a lot of rough-riding on Cooplacurripa years ago.

I do not want to blow about myself as a rough-rider in my young days, but I can honestly say this, that I could generally keep in sight of the best of them. The two roughest stations I ever rode on were Giro and Glenrock. They had some splendid horses on both those stations in my young days— no better’ or more spirited animals ever looked through a bridle. . .

My experience of bush riding is that you will find a lot of good riders downhill. However, where the good riding and judgment count is going round steep sjdings and into steep gullies ”at a good bat.”

TOM THE MAILMAN

To get away from rough-riders for a moment, might I mention another matter. Many years ago, Tom Briton used io run’ the mail’ from Gloucester to Walcha. He carried the mails, of course, on horseback. Tom was a hard old case and could pitch a good yrn with the best of the hands of his day.

Tom used to stop at Nowendoc at night— at Mr. Thomas Laurie’s— and he frequently had a great job crossing the rivers in flood time. He had to cross the Little Manning but went round the rest of the rivers. Whenever he came to a flooded stream, and he was mounted on his well-known black pony, Tom Briton was never afraid to put the animal into the stream. He used to reckon this animal was the best thing he ever saw in water. Tom said he would sometimes come to a river, find it was running a banker; but he would secure the mail matter, put it in bags, tie the bags up tightly, and fix them securely to the saddle.

Then he would put the black pony into the stream. Tom used to say that the only thing that troubled him was holding his breath long enough—as the mare used to ‘walk straight across the bottom of the stream.’ Tom swore by the ashes of his fathers that many a time ‘he ‘ ‘heard’ the logs’ clinking over the top of him.’

SNOWSTORM.

On one occasion Tom Briton went on to Walcha, and a heavy snowstorm came on. Coming back from Walcha with the mail, he lost his track in the snow. He got two miles out of his course, and then ‘struck’ a fence. Fletcher’s boundary rider from an ad joining station was on his rounds, and saw a horse tied up to the fence and covered with snow. The boundary rider went up, brushed the snow off the bags, and off the pony, and discovered it was Tom the mailman’s property.

Eventually the boundary rider found old Tom Britain lying against a big log. Tom had half a bottle of rum lying alongside of him. The boundary rider pulled the cork out of the rum bottle. Tom could not speak, nor could he open his mouth. It was frozen. So, nothing could be done with the rum just then.

HOT WATER.

The boundary rider got Tom on to his own horse and led him down to a hut about two miles distant. There he got Tom off the horse, and laid him down inside the hut, whilst he made a fire. He put on a quart of water. It was soon pretty well. boiling. He poured some of the hot water on Tom’s mouth, and through the medium of the hot water Tom the Mail

man recovered his speech, as he was able to open his mouth. He was also able to sit up and take a little nourishment—liquid and otherwise. Tom stopped there till the rum was finished, and he felt all right. Then he proceeded on his way to Gloucester, little the worse for his cold experience.

HEAVY PARCELS.

Tom Briton was one of those kind good-hearted old mailmen. There was a woman on his mail route those days who was always asking Tom to bring heavy parcels up from Gloucester for her. One day she asked Tom if he could bring a flowerpot up for her. Tom’s reply was pretty effective. He said: ‘No, Missus, I have a plough and harrow to bring up next time on horseback with. me, so it will be quite impossible to bring a flower, pot without breaking it.’

That was the finish of requests from the woman in question to bring ‘cargo’ along from Gloucester— and Tom was not sorry.

Tom died years ago at Gloucester. He had many genuine friends amongst the old hands, all of whom had a good word for him and at least some of the readers of this article will remember him.