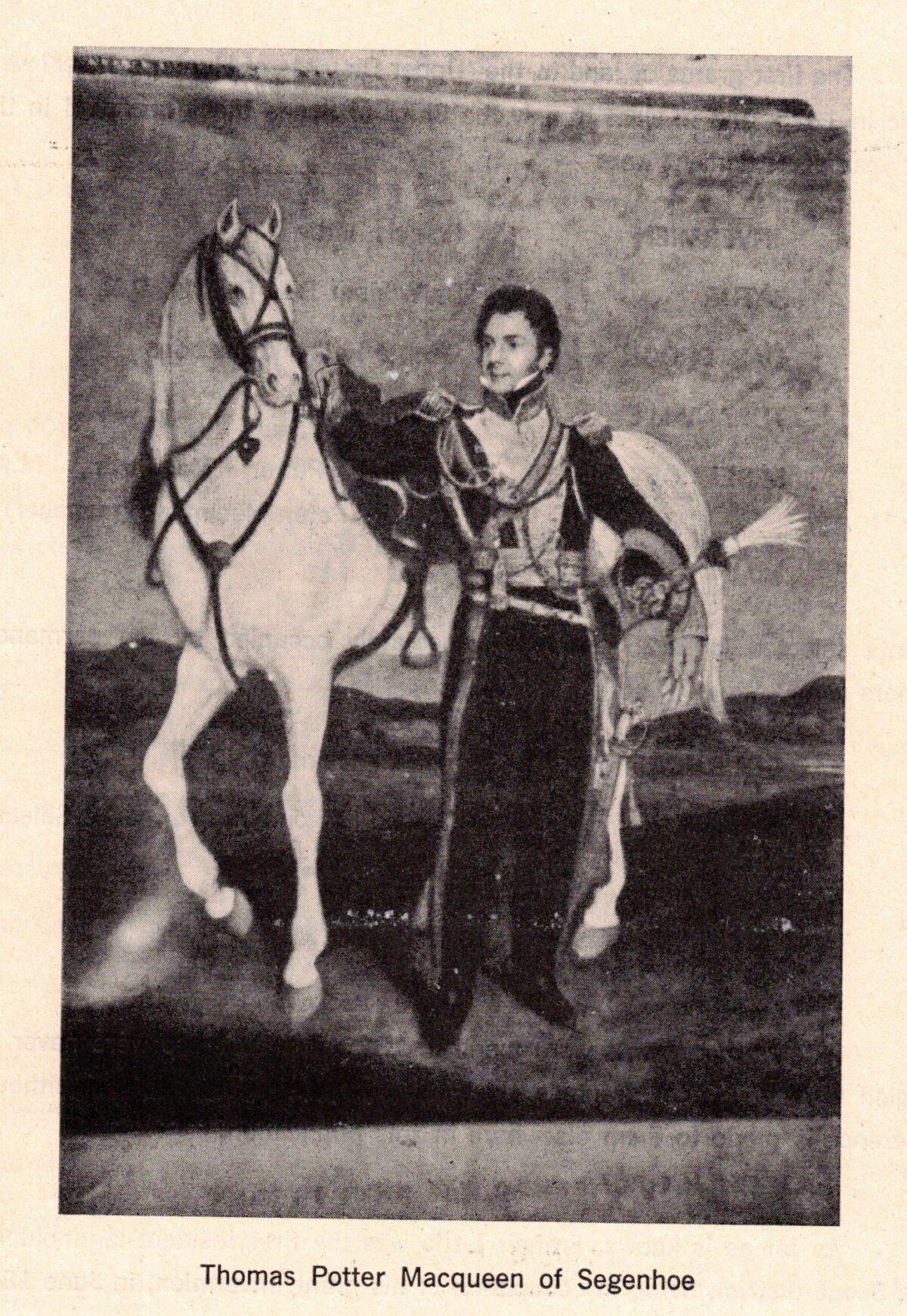

Thomas Potter Macqueen

Featured Image: Thomas Potter Macqueen

In 1825 Thomas MacQueen, a British parliamentarian, sent stock, supplies, machinery and workers including overseer Peter McIntyre and set up the Segenhoe Estate on land around Aberdeen. As the property was located at the then-northern fringes of settlement, explorers such as Thomas Mitchell, Allan Cunningham and Edmund Kennedy used it as a base for further explorations. MacQueen himself lived at the property between 1834 and 1838, lobbying the government set out a township. Aberdeen, named after the fourth Earl of Aberdeen who was a friend of Macqueen’s, was established in 1838. The single-story, stone Segenhoe homestead (circa 1830s) was constructed in Georgian style and is still in existence today (See Featured Image). A mill and an inn were operating in Aberdeen before 1840. The double-story, sandstone Segenhoe Inn was constructed in 1837 and is still standing. The ruins of the old mill also remain.

Macqueen, Thomas Potter (1791–1854)

http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/macqueen-thomas-potter-2420

By E. W. Dunlop

Thomas Potter Macqueen (1791-1854), politician and colonizer, was born in Bedfordshire, England, at Segenhoe Manor, Ridgmont, an estate which his father, Malcolm Macqueen, M.D., had inherited through his marriage to Mariana, only child of Thomas Potter. Thomas represented East Looe in parliament 1816-26 and Bedfordshire 1826-30. He joined the Bedfordshire yeomanry and reached the rank of lieutenant-colonel in 1820.

Macqueen read Commissioner John Thomas Bigge‘s report with interest, and was attracted by the prospects of rural settlement in New South Wales. He evolved a plan whereby the colony might be developed by settlers with sufficient capital to employ convicts on their own account. English landed proprietors were to be encouraged to buy land in the colony and send out some of their dependants to ensure ‘a wholesome population’, although the effective capital would thus be invested by persons not living in the colony.

Through the good offices of Earl Bathurst, Macqueen in 1823 obtained a grant of 10,000 acres (4047 ha) from Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane with a provisional reserve of a further 10,000 acres (4047 ha). Next year he appointed Peter McIntyre as his overseer and entrusted to him the selection and development of his grant. A carefully chosen party of mechanics, farmers and shepherds, equipped with farm machinery, stores, sheep, horses and stud cattle sailed in two chartered ships, Hugh Crawford and Nimrod, reaching Sydney on 7 April 1825. On Macqueen’s behalf McIntyre chose as his grant 10,000 acres (4047 ha) in the Hunter River valley, naming it Segenhoe after his employer’s birthplace. Under McIntyre’s guidance this quickly developed into a thriving agricultural estate. His work was continued by H. C. Sempill, who followed him as manager in 1830.

Macqueen’s venture of 1824 was the first direct shipment of free emigrants to New South Wales and gave a great stimulus to agriculture in the colony. He introduced experienced farmers and artisans, bloodstock, and the capital necessary for progressive farming. Between 1825 and 1838 he spent at least £42,000 on plant, stock and improvements on Segenhoe, and firmly established the Hunter valley’s reputation for efficient agriculture. During the drought in 1827-30 Segenhoe was the main source of grain for the whole valley. About 160 convicts were employed at Segenhoe, and Macqueen brought out some of their wives and families, numbers of them later becoming tenant farmers on the estate. Several of his employees, including the McIntyre brothers, Peter, John and Donald, Alexander Campbell, and Sempill, became pioneer squatters in the New England district. At the promptings of Macqueen the government laid out the township of Aberdeen in 1838, and the road to Segenhoe became part of the Great North Road.

Macqueen joined Thomas Peel, Sir Francis Vincent and E. W. H. Schenley in November 1828 in presenting a request to the British government for a large land grant at Swan River in return for carrying there 10,000 settlers from the British Isles. The association hoped to reap financial benefits from the cultivation of tobacco, cotton, sugar, flax and drug-producing plants, and grazing horses, cattle and swine. Macqueen offered the management of his prospective Swan River estate to Robert Gouger but by the end of January 1829 all except Peel had withdrawn from the venture.

Macqueen continued to advocate planned emigration. In 1830 he was a member of the National Colonization Society, which made the first formal attempt to organize the doctrines of systematic colonization in London. He published two short political tracts: The State of the Nation at the Close of 1830 (London, 1831) and The State of the Country in 1832 (London, 1832); both emphasized the poverty of the labouring classes and the severity of unemployment and advocated emigration, specially to New South Wales, as the solution.

In London throughout 1832 Macqueen tried to interest influential people in a joint whaling and banking enterprise; from this project sprang the Bank of Australasia. Thereafter he had little influence on its development although, in recognition of his initiating role, he was given a seat on the provisional board in London. He also helped to establish the Commercial Banking Co. of Sydney and became a director.

Meanwhile in 1831 a corruptly contested election had terminated Macqueen’s political career. Having sold his English estate to the Duke of Bedford, he went to New South Wales in July 1834. For the next four years Macqueen lived at Segenhoe and was a conspicuous figure in colonial society. He held office as a magistrate and had a town house in Darlinghurst. In August 1838 he sold his stock, leased Segenhoe, and returned to England where he published Australia As She Is and As She May Be (London, 1840).

At intervals between 1827 and 1841 he had been deeply in debt and there were suits against him in King’s Bench and Common Pleas. In 1845 he was living at Caen, Normandy, perhaps to escape his creditors. By 1852 he had returned and was living at Banbury, Oxfordshire, but all his estates had been sold. He died of apoplexy, at the Queen’s Hotel, Oswestry, on 31 March 1854.

At the New Church, Marylebone, on 26 October 1820, he had married Anne, sister of Sir Jacob Astley, baronet, of Melton Constable, Norfolk; they had two sons and three daughters.