The British East India Company in Early Australia and John Macarthur’s Influence in Colonial Horse Breeding

By Keith R. Binney, author Horsemen of the First Frontier (1788-1900) and The Serpents Legacy ©2006 Keith R. Binney. All Rights Reserved.

Edited extracts from Horsemen of the First Frontier (1788-1900) and The Serpents Legacy. Author Keith Binney; Hardcover ARP $59.95. At all good bookstores. Distributors Dennis Jones & Associates P/L.

See also: http://www.tbheritage.com/Breeders/AUS/AusHistBinney.html Visit Horsemen of the First Frontier for more information

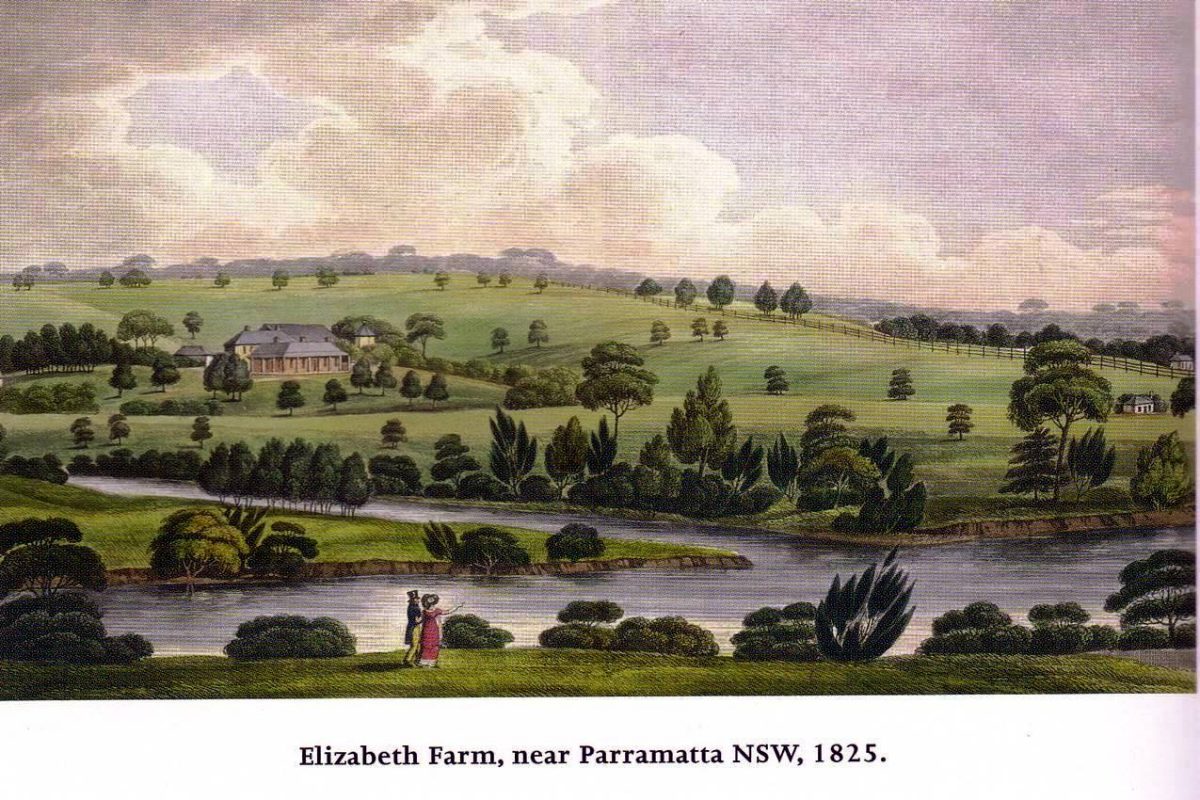

Featured Image: John and Elizabeth Macarthur’s Elizabeth Farm at Parramatta NSW, 1825

When one produces a broad historical work like “Horsemen of the First Frontier (1788-1900) & The Serpents Legacy”, perhaps the writer should not be surprised at any comments received. However, the number of Australian readers who have recently said things like “I didn’t know the British East India Company had anything to do with Australia” indicates a generally widespread gap in our historical knowledge of the early colonial period. This is especially so when the same people had learnt at school about the British East India Company’s major role on the Indian sub-continent, in the Opium Wars with China and with the “Boston Tea Party” of 1773, which was a precursor to the American War of Independence.

In essence, from the very inception of New South Wales in 1788, the Royal Charter of the British East India Company conferred an exclusive right on the Company to control all trade to and from the penal Colony. Further, the founding Governor, Captain Arthur Phillip RN, was specifically instructed to prevent private individuals from trading with India, China and the colonies of any European nation. To this end, the local building of any craft capable of such trading was expressly forbidden. Yet from as early as 1792, the E. I. Company’s monopoly right over all NSW commerce was being seriously flouted. However, the breaches were conducted in a subtle manner, being nothing as dramatic as when a party of American colonists dressed up as Mohawk Indians, boarded three British vessels in Boston Harbour and poured forty-five tons of tea into the sea. Early New South Welshmen were obviously much less flamboyant and dare we say, more discreet!

Largely through the entrepreneurial initiative of a 25 year-old, Lieutenant John Macarthur, aided by a complaisant Lieutenant Governor Major Francis Grose, in 1792 a consortium of NSW military and civil officers privately chartered the British supply ship and whaler Britannia. The charter fee was £2000 with a further £2,200 allocated as trading capital for the purpose of obtaining foodstuffs, livestock and general goods from the Dutch-controlled Cape of Good Hope. (£4,200 = $840,000 in 1998 AUD). Despite this being an obvious breach of the British East India Company’s Charter, the ailing Governor Phillip did not use his power of veto and thus the first of three private charters went ahead. Around the same time that Britannia was unloading its first cargo at Port Jackson in June 1793, during government talks held in London to renew their Royal Charter, the Chairman of the British East India Company Sir Francis Baring, expressed his strong feelings concerning “…..the serpent that we are nursing at Botany Bay.” As it turned out, junior officer Lieutenant John Macarthur was no doubt considered to be the “King Serpent.”

Nonetheless, this metaphoric expostulation by Sir Francis Baring did not stop contraband trading in the infant colony of New South Wales. It appears that colonial officials, who would normally be expected to record all arriving cargos, simply turned a blind eye to illegal shipments. Thus no official records were kept and the recipients of such imports were naturally, discreetly tight-lipped. This fact is clearly demonstrated by the livestock records of John Macarthur. From a speculative shipment of 100 fecund Bengal sheep that had arrived illegally from Calcutta in February 1793 aboard the Shah Hormuzear, John Macarthur received 30. Yet in a letter written to his brother James in England over a year later in 1794, in which John Macarthur listed his livestock in some detail, there is no mention of any sheep whatsoever. It seems likely that the shrewd and extremely smart John Macarthur was not prepared to create any written record that could later come back to haunt him. Further, in 1800 Macarthur offered to the government “a remarkable fine stallion from America for £650. This was in all probability the important foundation sire Washington, for which no record of importation appears to exist. How an official recorder could miss a horse valued in 1800 at £650 ($72,345 in 1998 AUD) at a time when shepherds were paid less than £10 per year, is a matter for suspicious conjecture. Regardless, all of these facts seem reasonable proof of the writer’s hypothesis that the reason the importation of early thoroughbreds like Rockingham and Washington was not officially recorded, is simply because – the horses were imported illegally.

Major Francis Grose resigned as Administrator of the colony in 1794, replaced on an interim basis by Captain William Paterson. In September of 1795 the incorruptible Captain John Hunter RN arrived in New South Wales as the new appointee as Governor. Hunter viewed John Macarthur as an officer with a “restless ambition and litigious disposition.”

To Captain Macarthur, the zealous Governor Hunter was an incompetent administrator, but perhaps more accurately, a real threat to Macarthur and his fellow-officers’ commercial activities. The Machiavellian Macarthur regularly sent direct to the Duke of Portland in London, serious written criticisms of Hunter’s alleged inept administration and extravagant expenditure of government money. In 1800, an unfortunate and bewildered Governor Hunter, who obviously did not expect such “behind the back” conduct from someone he considered a fellow-officer and thus a gentleman, was recalled to London. Hunter was the first but certainly not the last Governor to run foul of the nakedly ambitious John Macarthur, who by now was seducing those who passed for colonial socialites, with a litany of pious self-justification for his petty actions.

Following his assumption of vice-regal office in September 1800, Governor Philip Gidley King RN, just like his predecessor, immediately set out to try and break the New South Wales Corps officers’ powers by expressly forbidding them to carry on trade, particularly any dealings in alcoholic spirits. For whatever reason, but perhaps fulfilling his original intention of aping “the Botany Bay nabobs” in London, John Macarthur at this time announced that he was returning to England, and offered to the government all his livestock, and land holdings that he valued at a not unreasonable £4,000. The fertile, fully cleared Elizabeth Farm comprised nearly 300 acres and his total prime land holding was almost 1,300 acres. Not surprisingly, a still incumbent Colonial Secretary, the Duke of Portland, expressed concern that an officer on official duty should have been able over seven short years, to acquire such wealth apparently from part-time farming pursuits.

Fortuitously, from the viewpoint of anyone researching the history of the Australian thoroughbred, the interesting fact was that among his list of livestock John Macarthur offered ten horses. They included five mares of Indian descent (probably of mainly Arab blood, and thus more valuable than cape-bred ponies) at £65 per head, and in particular “a remarkable fine stallion from America for £650.” Almost certainly this hugely expensive American horse was Washington, which is thought to have been one of a shipment of coaching and cavalry bloodhorses described as being of Spanish-Eastern origin, imported to the Cape of Good Hope from New England around 1797-98. Washington is suspected, with good reason, to have been imported to Sydney in April 1800 by a private arrangement with Captain William Kent, commander of the HMS Buffalo. However, no doubt for the reasons previously stated, no official record of Washington’s landing was made. Thus, at this early stage of colonial history, Elizabeth Farm was the home of some of the very best bloodhorses and mares in the colony, even though some were obviously not pure thoroughbreds. A foal by Washington, especially one out of a mare by the earlier import Rockingham, represented the best bloodlines the colony had to offer at the time.

The sale of horses to the government did not proceed, and in a pre-emptive purchase Macarthur obtained 1,300 merino-cross sheep from a fellow officer, doubling the size of his own flock. By attempting to manipulate his superior officer, Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson, Macarthur precipitated a duel, in which he seriously injured Paterson. Governor King insisted the ensuing court martial take place in England. Macarthur set sail for London in a ship named the Hunter in November 1801.

During the period that John Macarthur was away, which turned out to be the next four years, a stoic Elizabeth Macarthur remained at Elizabeth Farm with her youngest children Mary, James, and William. Elizabeth was left to handle in her usual calm, competent manner, management of Macarthur’s pastoral affairs including sheep husbandry and horse breeding activities. At this point feminists could well rise up and ask — who in fact was the Elizabeth Farm studmaster and breeder of fine bloodhorses at what was then arguably the leading horse stud in the colony? Bloodhorses bred at this time included Percy (1804) by Northumberland (GB) from “a famous Trotting mare” and Hotspur (1805) by Northumberland (GB), a full-brother to Percy. Incidentally, auctioneer John Howe later offered both stallions for sale at a Windsor auction in 1812. From that date on, John Macarthur became a regular vendor of high-class bloodhorses, particularly stallions. The bloodhorse sire Percy (1804) by Northumberland (GB) stood for a time at James Badgery’s Exeter Farm at South Creek.

By the time the Hunter reached England in December of 1802, the ship carrying Governor King’s emissary with details on the court martial had disappeared at sea. While both Macarthur and the colonial administration in Sydney were officially censured, it was made clear to King that charges against Macarthur should be dropped. While in London Macarthur promoted the use of Australian wool, of a finer quality than English wool, the demand for which had increased with the need for clothing and blankets for the army, at that time engaged in the Napoleonic Wars. Macarthur composed a “Statement of the Improvement and Progress of the Breed of Fine-woolled Sheep in New South Wales,” establishing himself as “the supreme authority on and industry representative in England for all of the fine-wool producers in New South Wales.” With a network of political allies in place, bolstered by the patriotic mission of raising wool to clothe the army, Macarthur resigned his commission and returned to Sydney in 1805. He brought with him a recommendation that he receive a grant of 5,000 acres of the best grazing land in the colony (with a further 5,000 acres to be granted when returns were forthcoming). He also brought nine Spanish merino rams and a ewe obtained from the Royal flocks at Kew with a special dispensation from King George III for export. A disillusioned and ill Governor King resigned and was replaced by Captain William Bligh RN.

The Macarthurs retained Elizabeth Farm at Parramatta and set up Camden Park in the new district of Camden, both latter areas having been named in honour of Macarthur’s benefactor, Lord Camden. John Macarthur proceeded to attend to his pastoral and mercantile interests at Elizabeth Farm and transferred most of his horse breeding activities to Camden Park. Unfortunately, while better tha most, the written Macarthur records on horses are often sparse in detail, especially for mares. However, there is no doubt Camden Park was a very significant, if not more likely, the major breeder of bloodhorses in the colony at the time. In the 1804 livestock census, Captain Macarthur is credited with owning 12 horses and 14 mares out of the total of 404 horses of all types in the whole colony. By comparison, in the year 1800 there were only two horses in all of Green Hills (later Windsor). Interestingly, both were owned by emancipists, viz. Andrew Thompson and Thomas Rickerby.

It seems that the American horse Washington had only a short career at stud. Nevertheless, it is obvious that his female progeny provided most of the foundation broodmare band, which in a short time established Camden Park stud’s reputation as a supplier of first-class saddle and carriage horses. As well, the stud catered for the emerging demand for racehorses, of which they were major suppliers. Another prime Camden Park stud influence was the Lieutenant-Colonel George Johnston-imported coaching sire Northumberland (GB), which spent from around 1809 until his death in November 1812 at Camden Park. It should be appreciated that the female progeny of many of the sturdy pony-sized Cape and Bengal mares, arising from matings with such fine big coaching horse sires, formed the taproot mares appearing in the pedigrees of the early racehorses. This quick upgrade in quality is not really surprising when it is considered that only three crossings of successive progeny with superior stallions reduces the original mare’s genetic contribution to one-eighth of the gene pool and with reasonable luck, her vital influence has diminished accordingly. The same principles were used in upgrading Macarthur’s crossbred sheep flocks, with pure merino stud rams being put over Bengal sheep and their progeny, to eventually provide the finest grade of wool producers.

Macarthur and Bligh, natural antagonists, clashed over such issues as the development of Camden Park with convict labor and Macarthur’s various commercial activities. Macarthur supported Major George Johnston in the “Rum Rebllion” of 1808, in a dispute with the New South Wales Corps officers over control of the liquor trade. Bligh was deposed and Macarthur installed in a newly-created position, “Colonial Secretary.” This lasted until a new administrator, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Foveaux, arrived to take command. In 1809 Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson (victim in the duel) became acting-Governor. Macarthur set sail for London again in March of 1809 to assist in the defence of Major George Johnston, and to continue his promotion of the colonial wool industry and advance his mercantile interests.

Meanwhile Elizabeth Macarthur assisted by her nephew by marriage Hannibal Hawkins Macarthur and an emancipist overseer, the admirable Richard Fitzgerald, continued to manage Elizabeth Farm, Camden Park, and the other family pastoral holdings. H.H. Macarthur had also received a grant near Camden that he named Arthursleigh, which for some time was the southernmost grant in the County of Cumberland. Besides her growing expertise in sheep husbandry, the well-educated Elizabeth was also in charge of the horse breeding activities. Early on, the sire Derwent (Arab) by the Tasmanian based White William (Arab) had been used at Camden Park. A homebred sire at this time was Derwent by Derwent (Arab) by White William (Arab) from a mare by Washington. Others were Holkar (1817) by the Macarthur-bred Percy (1804) by Northumberland (GB) from “an imported Indian-Arab mare” and Marmion (1817) by Percy from a mare by Washington. Also, Oscar (1817) by Percy from a mare by Washington. The importance of Washington mares at the premier stud of the colony is obvious. By the early 1820s, John Macarthur was listed as owner of more than 100 horses, and was the major supplier of prime bloodhorses in the colony.

Macarthur would not return to New South Wales until 1817, after which he had additional, serious run-ins with successive governors, served as a legislative representative of the first Legislative Council (1825), received gold medals from London for the quality of his fine-wool, and saw Camden Park expand to include over 60,000 acres of land, aquired by both grant and purchase. He gradually descended into madness, and died April 11, 1834. His sons, James and William Macarthur, became the leading breeders of thoroughbreds at Camden Park in succeeding years. For some of the colonial female families they developed, see Family C – 1 and Family C – 12.